Bob Marshall, Edward Abbey, and the art of life as work

Two wilderness icons and the odd way I followed them

Of all people, it was Edward Abbey who best embodied the freelance-writer-as-capitalist: he insisted on getting paid three times for the same set of sentences.

Abbey, of course, is known as a freedom- and wilderness-loving anarchist. Some people get frustrated with his proto-Trumpian stances against immigration, feminism, and politeness. Others love the brilliance of his sentences. He aspired to be an aphorist, and thus wrote lines like, “To avoid steady work for half a century, as I have done, requires talent.”

As that line implies, he was the opposite of a careerist. People remember him for glamorizing the life of the wildland fire lookout: basically doing nothing all summer long in the middle of nowhere, while hopefully getting paid enough to survive on rice-and-beans until you have a chance to maybe do something like that again next year.

Late in his life, Abbey got a job teaching nonfiction writing at the University of Arizona. He turned out to be so good at it that they promoted him to full professor (“fool professor,” as he kept calling it). Biographer James Cahalan quotes Abbey as telling students in 1980 that he had “discovered that I could sell each thing I wrote… three times—first as a reading at some university, then as a magazine article, then as part of a book.”

By that point, he was treading on his reputation. Abbey was like Hunter S. Thompson: he gained fame for speaking a deep inner truth. Then he realized that the “me” doing the speaking was something of a performance—but he was stuck because his audience insisted that he keep playing that role, or even exaggerating it. So his lectures were often packed, but he was often drunk. Once he even paused to wave around a gun.

Nevertheless, the lecture usually had a text that he was starting from, and he would then sell that text to anyone who would buy it—obscure journals, Playboy, Penthouse, Sierra Club calendars, coffee-table photo books. Later he’d repackage the essays in anthologies. When the anthologies got reviewed, critics often acted as if they were experiencing these words for the first time, which they probably were. Abbey deserved all three paychecks because each brought his work to a new audience.

By the time I started freelancing in the 1990s, Abbey's advice had become common wisdom: turn your expertise into multiple paychecks. For example, the Northern Cardinal is the official bird of seven different states, so if you could write one good article, you might could sell it to seven different state wildlife magazines.

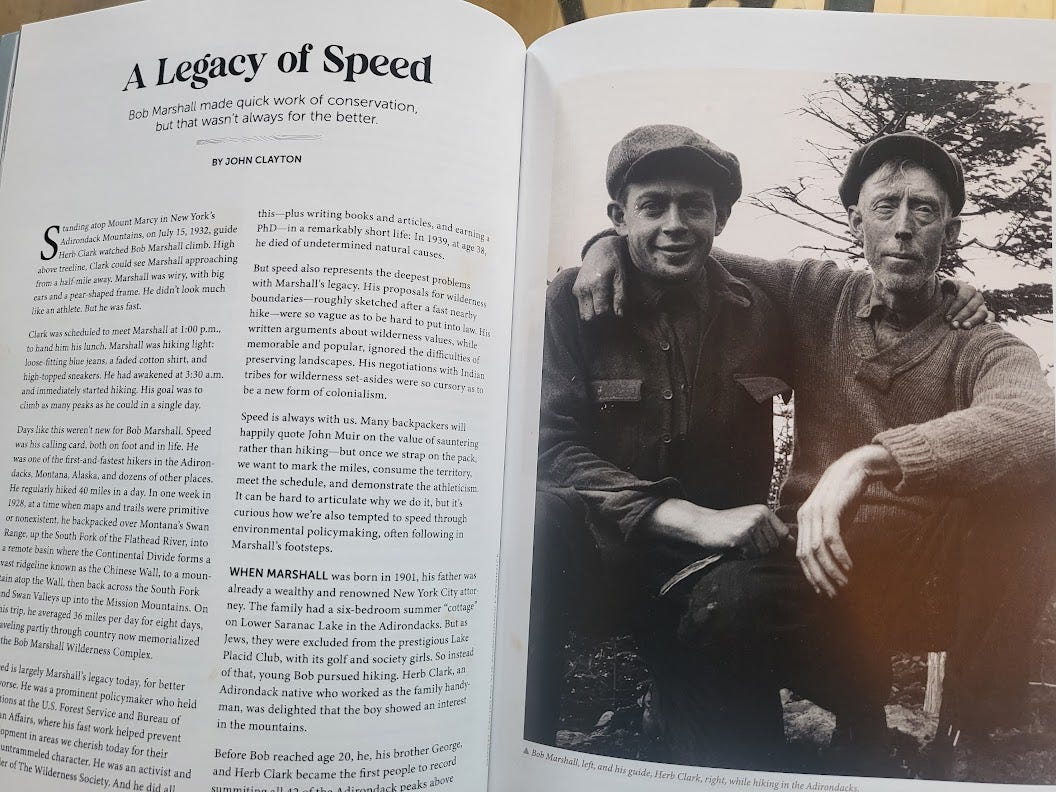

I was never very good at this game. But I’m trying to get better. This month I published an article about the wilderness legend Bob Marshall in the beautiful print-only Trails Magazine. I’ve written about Marshall before, both here on Natural Stories and in the print-only Montana Quarterly. I’m not republishing the same article like Abbey did, but I am leveraging the same research to tell new stories.

Without giving away too much, I’ll say that the Trails essay focuses on how the style of Marshall’s work—writing wilderness policy for the US Forest Service and Bureau of Indian Affairs—matched the style of the rest of his life, including his 40-mile-a-day hikes and his volunteer advocacy in founding the Wilderness Society. Both his strengths and weaknesses were evident in both his work and extracurriculars. It’s as if there were no lines between them.

I realized: that union itself is a form of art. To have a career that so perfectly matches your interests, to have strengths that so resemble your weaknesses, to have hobbies that prove so useful in your job, to build your passions and networks out of all of that—it’s like a piece of landscape art, or a song, or an abstract expressionist painting. It’s beautiful and emotionally moving.

Marshall didn’t have a 9-to-5 job. Or rather, he had one, but it was so well integrated to the rest of his life that it was indistinguishable from the other expressions of his core creativity. No wonder he’s such a fascinating man.

A second realization: Abbey made the same kind of art-as-life. A third: I aspire to it myself. The writing and the hiking, the researching and the camping, the reader-friends and the writer-friends and the networks. The desire to parlay my Marshall research into multiple paychecks by bringing it to multiple audiences.

To blur the lines between work and life is not necessarily fulfilling or productive or emotionally healthy. But to the extent that a person can pull it off, its integrity shines with a challenging, inspiring beauty. It feels like a natural story.

Discussion:

And of course here I’ve done it again: parlayed my Marshall research (…plus my Abbey research …plus 30-some years of freelance experience…) into a new essay for a different audience. Thanks for reading!

I quote Abbey from James M. Cahalan, Edward Abbey: A Life, pages 103 and 196. I get a slight commission when you click on affiliate book links, but I’m just as happy if you buy from a local independent bookseller.

I feel blessed to be part of Trails at just the moment where it deserves to pick up a bunch of readers dismayed at the decline of Outside. Kudos to Stasia, Ryan, and the Trails staff.

Given my druthers, we'd have a society in which blurring the lines as you (and Bob and Ed, and even I, sometimes) do would not be odd. Or maybe we wouldn't even perceive the career-life line?

What month of Trails Magazine has the feature on Bob Marshall?