The swoops and swirls of natural stories

The abstract painter Jackson Pollock was a thoroughly urban artist. So what do we mean when we talk of his nature?

In the New York City art world of the late 1940s, Jackson Pollock was seen as a force of nature. He was a “hard riding hard drinking cowboy from the Wild West who came roaring, maybe even shooting, his way into New York,” one biographer wrote. The biographer was speaking more of image than of fact, but then Pollock was an artist, not a historian. Indeed people saw Pollock as a “natural” artist: undertrained, undereducated, not conventionally talented, but expressing deep inner emotions.

Although Pollock continually highlighted his Wyoming birth, he left the state before his first birthday. His family kicked around California and Arizona—generally in relatively urbanized areas—for most of his youth. In 1944, an interviewer from Arts and Architecture magazine asked why he lived in New York. Pollock admitted that he had “a definite feeling for the West: the vast horizontality of the land.” But in New York, “the stimulating influences are more numerous and rewarding.” That meant “Living is keener, more demanding, more intense and expansive.”

Most dyed-in-the-wool New Yorkers have always been born elsewhere. They seek that stimulation, that sense of keen expansiveness. If we ask about the influence of, say, their native Cincinnati, they shrug and say life really began when they arrived in New York. But Pollock knew how romantic the West seemed to midcentury Americans. “My father had a farm near Cody,” he lied to the New Yorker in 1950. “By the time I was fourteen, I was milking a dozen cows twice a day.”

When the Arts and Architecture interviewer asked if being a Westerner affected his work, Pollock responded with admiration for “the plastic qualities of American Indian art.” (Recall that in the 1940s, plastic had more positive connotations than today.) “The Indians have the true painter’s approach” to choosing subject matter.

Navajo sand painters worked directly on the floor, as Pollock later did. But he saw them employing this technique at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, not in Arizona. And at least in this interview, he didn’t talk about technique. He appreciated Indians as artists. “Their color is essentially Western, their vision has the basic universality of all real art,” he said.

It was a remarkable statement. At the time, most Americans referred to Indigenous people in the past tense, as if their cultures had already vanished. Most wanted to place Indians on a reservation, carrying a tomahawk while wearing a headdress. Pollock appreciated them as working contemporary artists, just as capable of influencing him as Picasso was.

But then Pollock was an abstract artist. He strove to see art for itself, not for its story.

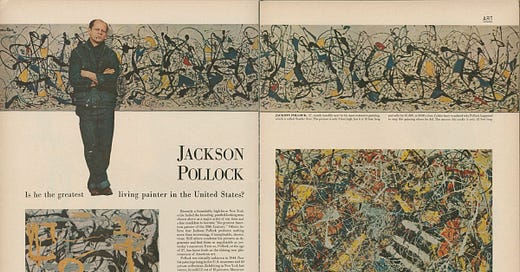

Explaining why he stopped giving conventional names to his paintings, Pollock told the New Yorker, “Abstract painting is abstract. It confronts you.” His wife Lee Krasner—also an artist, and far better at talking about art—explained that instead of titles, he simply numbered the paintings. “Numbers are neutral,” she said. “They make people look at a picture for what it is—pure painting.”

Yet we can’t. To me, the most powerful aspect of Pollock’s art is the way it impels the viewer to try to impose a story onto it. We look at the drips and swirls, the swooping curves, the clots and pools—and we think it must be nature. See the connections? Like an ecosystem! See the soaring lyricism and cascading intensity? Like a landscape! See the chaos? It’s actually fractal!

I’m not interested in whether or not those answers are true, or intended. The point is that the artworks themselves lead us to the questions. And that we center the questions on story. We see drips and swoops and tell a story about that art—often art as nature. We learn that Pollock was born in Wyoming and tell a story of the West—often the West as nature. We learn that he admired Indigenous artists and impose a story—often a story of Indigenous people as “natural.”

The abstraction of Pollock’s art reveals: stories are our nature. The subjects of those stories reveal: we see nature as a story.

Notes:

Pollock quoted in “Jackson Pollock: A Questionnaire,” Arts and Architecture 61, No. 42, February 1944; Pollock and Krasner quoted in Berton Roueché, “Unframed Space,” New Yorker, July 28, 1950, both reprinted in Jackson Pollock: Interviews, Articles, and Reviews, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1999. Biographer B.H. Friedman quoted in Jackson Pollock: Energy Made Visible, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972.

For the full story of Pollock’s Wyoming connections, see my piece at WyoHistory.org.

Egads, this is great, John. Thanks for sharing. I've been circling around Pollock's legacy as well, thinking about how he was one of the modernists to reach the west and influence artists out here. Neil Jussila once told me when he not yet 18, he was sitting with the older artists in a bar in Butte, and one of his idols described abstract expressionism and Pollock's work as the Chinooks that come to break the city from its winter grasp. I've loved that image since Neil shared it with me, and it certainly explains Neil's influences as well.

Hard to throw a rock in the American West without hitting a pile of mythology.