Bob Marshall’s flaws make his story more natural

I wrote about the man, and remembered my misery in the area that commemorates him

My stove wouldn’t provide much heat. My matches were for shit. And the mosquitoes were absolutely unbearable.

I was taking my college friend on his first western wilderness excursion. I felt the burden of being the alleged expert, as I’d been backpacking before. But I’d always had more experienced companions. Now I was failing. Without meaningful heat from the stove, warming up dinner would take forever, likewise coffee tomorrow morning. Perhaps, if just one of these matches could do its job, we could light a fire for those purposes. Then the smoke might even keep away the mosquitoes. But the climb had been steeper than we’d expected. My friend wasn’t acclimated to the altitude. We were exhausted. Between the exhaustion and the mosquito whine, we could barely think straight.

It was probably my most miserable wilderness experience—and yet memorable for that reason. Any great story involves hardship. You have a goal; you conquer obstacles to meeting that goal. You develop greater bonds with your co-adventurers; you learn something about yourself. You grow. One of the reasons so many people love wilderness recreation is that it provides opportunities for that growth—for those natural stories.

That trip gave me plenty of growth, with most of it centered on hubris, equipment, and mosquitoes. But the trip was also interesting for its goal. We were headed to the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

Last week I published a story about Bob Marshall. Montana Quarterly teased it as “the Bob Marshall you don’t know.” Because while most Montanans are familiar with the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, a place of legendary backcountry beauty and scale, the man it’s named for is a bit mysterious. I hadn’t known much, myself, until I started researching the article. After all, Marshall died 85 years ago. He was only 38 at the time. And his legacy was arguably greater in the Adirondacks, where he grew up, or in Washington DC, where he spent most of his career.

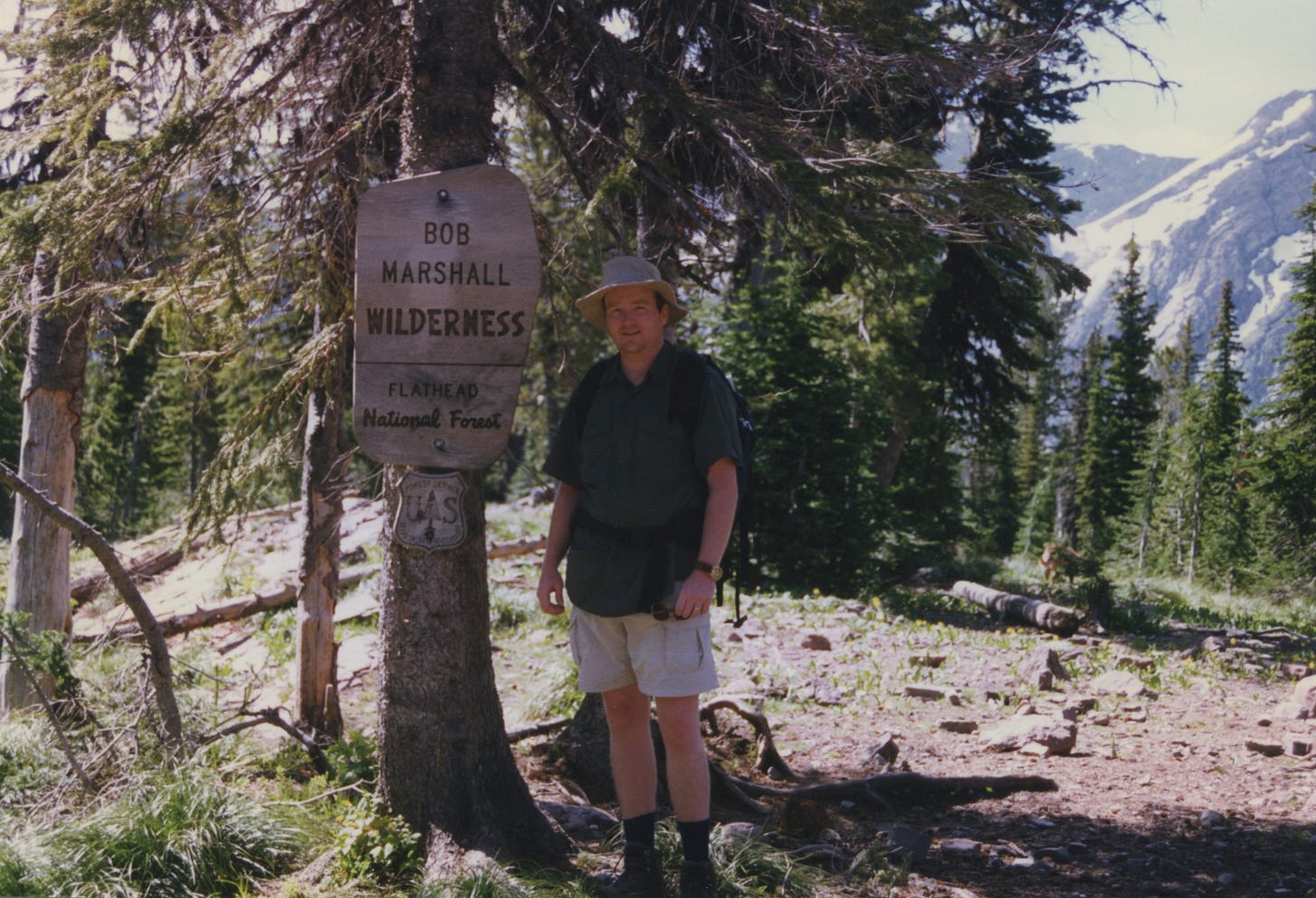

On our backpacking trip, my friend Chasmo, a professor from upstate New York, noted that some of his students were familiar with Marshall as one of the first people to summit all of the Adirondack peaks above 4,000 feet in elevation. (There were more than 40 of them, only 14 of which had trails.) If I took Chasmo’s picture in front of the sign at the wilderness boundary, his students would be able to see that Marshall also had a policymaking legacy half a continent away.

I was happy to help Chasmo in his quest. But the goal seemed a bit crazy to me. How could you come to Montana, be surrounded by so much nature, and take a picture of a sign? How could you be in one of the most completely preserved mountain ecosystems in the world and focus on an old dead white man, instead of all the ecological wonders we imagine when we say the world wilderness?

My doubts only grew years later, when I dove into the research for this article. Marshall’s short career, it turns out, was marked by some pretty big mistakes, which have been long hushed up. Worse, those mistakes centered around the conservation movement’s relationships toward Indigenous people. Bob Marshall was not a racist. But some of his actions ended up harming tribes, as well as the wilderness cause he so loved. (I won’t get into the specifics here—that’s what the article is for.)

From the moment I took Chasmo’s picture, more than 25 years ago, I’d been conflicted about Bob Marshall. Who was this man? What was the story that warranted him getting the honor of having a wilderness named after him? “Backpacked in this area” and “worked for the Forest Service” and “died at 38” didn’t seem like sufficiently worthy accomplishments. Only in seeing his failings did I grasp his story.

Marshall was flawed, as we all are. He pursued his passions, as we all aspire to. Watching him learn, and grow, and try (and fail) to overcome his own flaws in pursuing goals that were important to him—that’s a natural story. More than his policy accomplishments or hiking exploits or his recipe for “broiled eggs,” the natural story is what makes him likeable.

I made mistakes on our backpacking trip, but Chasmo was willing to do more with me. I was miserable in the wilderness named after Bob Marshall, but I want to go back. Marshall made some really bad choices about wilderness policies on Indian reservations, but our subsequent reluctance to tell that story almost turned him into an anodyne figure seemingly unworthy of his honors.

Discussion:

The article (paywalled) is at https://www.themontanaquarterly.com.

A great biography is James M. Glover’s A Wilderness Original: The Life of Bob Marshall. Paul Sutter’s Driven Wild also nicely captures Marshall’s impact. Marshall’s nonfiction chronicle of Alaska, Arctic Village, makes “Northern Exposure” look like “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.”

In the comments, I’m particularly interested in your thoughts on Marshall’s character, his legacy, or your own wilderness misadventures.

Well, there was the time two summers ago that Gwen and I did not properly assemble our inflatable kayak and sank in Lower Saranac Lake, where Bob Marshall's family once had its "camp." Fortunately it was warm, the shallows were near, and we enjoy each other's company even when dragging a soggy, floppy boat-thing along the shore.

I am not sure that gives me any connection to Bob Marshall, who is prominent (hard to avoid, really) in Adirondack outdoor history. But of the Wilderness Society's founders, I think he best represents the question of the relationship of wealth and wilderness. I have two questions for John. First, did he radiate his privilege? Which I guess, is a question about what he was like in person? Second, did the privilege afforded by wealth contribute to his failures?

I was once deemed the expert of a backpacking excursion, too. My dad used to pick me up from elementary school (which was an environmental science charter school in Oregon) and take me hiking or disc golfing or foraging through the woods. He told me to keep up or I'd get left behind.

By 2020 I had gone on a few backpacking trips but all of them were routed around Forest Service cabins. I always carried a tent but never used it until this trip with my dear friend, Rachid. He relied on me. I've always been an outdoorsman. After a few rugged miles we reached our destination for the night in the Spanish Peaks. We chose a place to set up camp then walked back down a little ways to hang our food, as good outdoorsmen do. It was almost dark. Across the basin we saw a dark figure waltz along the treeline. All evening we'd been yelling, "Hey, bear!" An encounter with a bear had been reported earlier that week. We were camped above where we saw what we thought was a bear and decided we shouldn't hike back out. So we stayed up all night, petrified that our first "real" backpacking trip would be our last.

We were up with the sun and already packed up when my friend took a phone call (he's a hot shot lighting designer and must always be reachable). To maximize his reception, he stood on a boulder on a hill just above where we'd been camping. On the other side of the boulder there was a person who had slept in his hammock the night before, surrounded by his snacks and a tiny smolder of a fire. We took every precaution while some dirt bag decided to luxuriously lounge just 50 feet away from us. Angry and under slept, we huffed and puffed back down the mountain. Less than a mile down, I quickly call my dog back to me and tell Rachid to grab his bear spray. There was a mountain lion on trail in front of us. My outdoorsman confidence had been rocked for eight hours straight before, but in the matter of four seconds, my title was restored. I was always prepared. The lion let us be. We made it home safely. I've always been an outdoorsman. Now I continue to work on my bravery.