The natural source of Joe Lockhart’s wealth

Following the money behind an Illinois pioneer hero

To its earliest white settlers, Elkhorn Grove was a primeval forest. These people found towering maples, oaks, and black walnuts four feet in diameter; woods dense enough to hide herds of deer; flocks of prairie plovers, crooked-billed snipes, geese, ducks, brants, and "sandhill cranes dancing a cotillion," in the words of local historian George Thiem. It was an oasis on the prairie of northern Illinois, and its wildness meant that it was the frontier.

Those early settlers built a sawmill and felled the trees to make wood products: beams for plows built by the nearby Grand Detour Plow Company, owned by a man named John Deere. Barrels to ship the pork and flour grown on the plowed prairie. Houses in nearby villages. Fork handles and wooden rakes and spinning wheels, tables and chairs and bureaus. The forest was waiting for the application of hard work to become profit, and such opportunities meant that it was the frontier.

Though not one of the first settlers, Joseph Cameron Lockhart believed in those frontiers. He was a taciturn man, dark-complected, five-foot-nine, with black hair and black eyes. His hair was full and thick, his moustache bushy. He'd grown up in northeast Pennsylvania, Luzerne county, where his father, a merchant, had died young. As the oldest son, Joe finished high school in 1856 and immediately joined the flood of pioneers moving to Illinois. (In 1850 the state had felt practically empty; by 1860 it was the fourth-largest in the union.) Joe, at 18, became a merchant based in the nearby town of Polo, which was booming with a new railroad line.

Polo founder Zenas Aplington, a generation older than Joe, must have served as a role model. Aplington, too, had come to the Polo area as a young man, in 1837. His first job was in a sawmill. Over the next 25 years he worked as blacksmith, carpenter, sawyer, farmer, railroad contractor, merchant, real estate dealer, legislator, and soldier. With money he bought land. With land he bought prestige.

When a village named Buffalo Grove refused to give the railroad a right-of-way, Aplington did. The railroad put a station on his farmland, a mile northeast of Buffalo Grove, and he moved a house there. He platted a town and named it after an Italian explorer. Folks raised cattle on the nearby prairies, cattle and hogs and grain, and brought them to Polo to ship. The town thrived, while Buffalo Grove withered. One night, in the middle of the night, somebody picked up the Buffalo Grove post office and moved it to Polo. The coup was complete. Aplington became a rich man—but, to the community, a generous one. He headed the town's board of trustees, headed the drive to establish a high school, and gave money to every single church that sought to build in Polo.

Joe Lockhart followed the path of the early Aplington, working at various jobs, buying and selling things. He would travel through Illinois and Missouri, buying mules, and return to Polo to sell them. By all accounts he was a shrewd businessman. He worked hard, played by the rules, treated people fairly—and accumulated wealth.

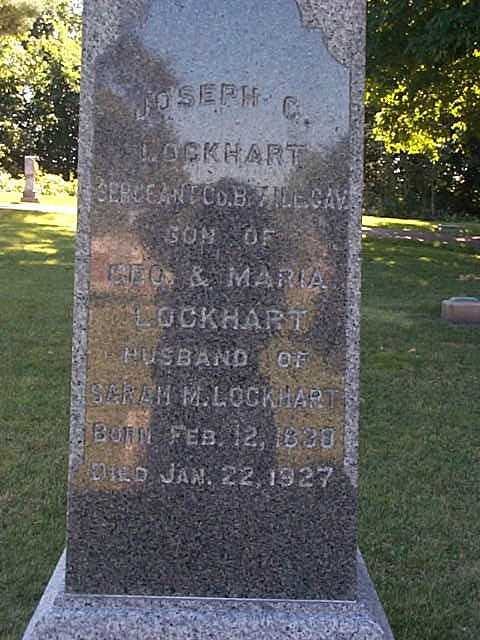

I first became interested in Joe because after serving under Aplington in the Civil War, he returned to Elkhorn Grove, married, and fathered a child named Caroline. She later became Wyoming’s most famous novelist, journalist, and rodeo founder. Her father’s wealth buoyed her through hard times.

To Caroline, the source of her father’s wealth was his character: incredibly smart, hardworking, ambitious, individualistic, unsentimental, unemotional, even cold. He wasn’t exactly fun, but he showed his love by being a good provider. He epitomized the self-reliance of the pioneer, the glory of the frontier. He later moved to Kansas, because it was more frontierlike, and where Caroline had more room to ride horses. Joe kept trading, now mostly land rather than mules, until at one point he became the state’s largest landowner. Caroline later tried to mirror those lessons on her own Wyoming and Montana frontiers.

Yet to me, the source of Joe’s wealth was nature. The land itself. The mules to work it. The lumber cut from those groves. The crops grown on those soils. The horses and cattle eating that grass. None of Joe’s moneymaking schemes would have worked if he hadn’t come across a land rich with natural resources, and reaped them.

Sure, the railroads played a role. The construction of sawmills. The development of laws and an administrative state to track things like who owned which parcel of land. The character of people like Joe Lockhart and Zenas Aplington who built such institutions, for their community’s benefit as well as their own. But if they had not come across these “empty” and “unowned” lands—which in fact had been sustainably stewarded for centuries by Indigenous people they ignored—those character traits would not necessarily have led to the same results.

Joe wasn’t a bad man, not at all. He played by the rules of the society he saw around him. In this sense he differed little from most of the people of his era, including my own ancestors in Ohio and central Massachusetts. But those rules had some problems. They were tilted away from justice for people of color, and away from sustaining the natural bounty that provided the source of these men’s wealth.

Before Caroline’s second birthday, opportunities to tame wilderness had dried up. The last deer in Elkhorn Grove had been killed. A nearby village had been nicknamed Stumptown. The black walnuts were gone, the maples and oaks and birds were all gone. A few years later, the Joliet Match Company would come in to take the useless basswood, the stuff nobody wanted, and chop it up into tiny firestarters.

Joe Lockhart loved Elkhorn Grove. After almost fifty years of living in Kansas, he would choose to be buried in the Polo cemetery. But in the moment, when he perceived that this wilderness had been tamed, the oasis denuded, the nature beaten down by people like himself, he left for Kansas because his personal nature required a new source of wealth.

Notes

I tell the Lockharts’ story in The Cowboy Girl. I explore the dual meanings of frontier (a place of adventure in nature, or a place of resources to reap) in Stories from Montana’s Enduring Frontier.

E. George Thiem’s 1968 county history is Carroll County: A goodly heritage. Zenas Aplington’s story is in the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for his home in Polo, IL. To imagine old-time Elkhorn Grove, you can visit the nearby Elkhorn Creek Biodiversity Preserve. For similar stories, set about 100 miles east, see William Cronon’s incredible book Nature’s Metropolis.

Welcome to those of you arriving from the recommendation at Craig Lancaster’s great (old-school) blog. You can learn more about Natural Stories at the About page, peruse the archives, and feel free to leave a comment.

Yes! So, the question I ask, is why were those bounteous resources not everyone's natural heritage to be shared? The people who were there before operated an economy of sharing for generations without depleting the resources. Then, suddenly, those resources were mostly gone within one generation. I see no sense in assigning personal blame to men like Joe (I do assign some to the philosophers who stood behind them, John Locke should have known better). They were creatures of their culture and the times and were often fair and generous within their context. But of all the things the settlers brought (disease, violence, etc) the worst was the story that the forest (etc) was a resource, not a relative.

Interesting, albeit sad, read. Prior to the arrival of European invaders (or the other native American tribes pushed west by those Europeans) Illinois was significantly peopled. Would have been interesting to see the character of the area before Europeans had much impact in North America.