Origins of Howard Zahniser’s wilderness crusade

How a Bighorn Mountain adventure shaped the 1964 Wilderness Act

This month I’m publishing a major new article, “Howard Zahniser’s Wilderness Awakening,” in Big Sky Journal. You can read it free here, although as usual I prefer the stunning presentation of the dead-tree edition. In this space I’d like to give some background on how I came to the story and why I cared.

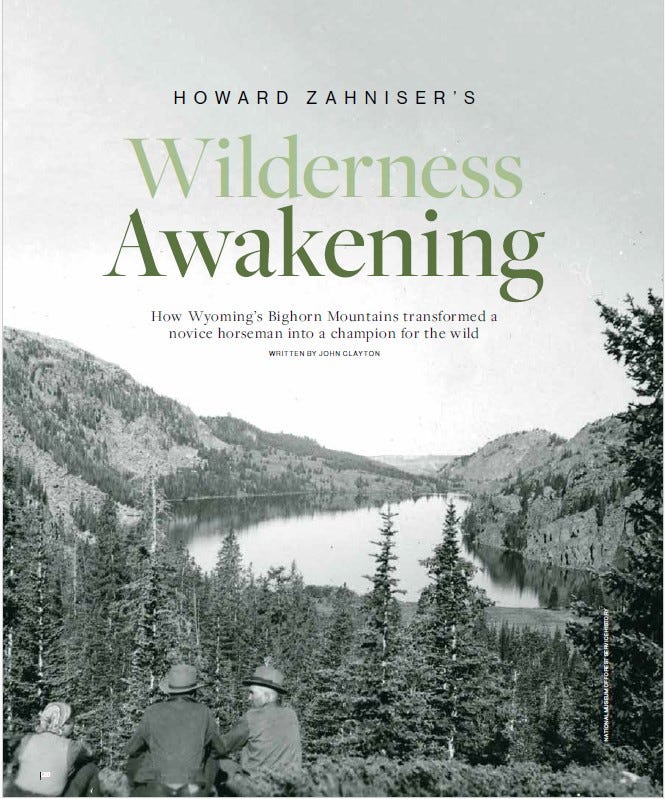

Environmental historians view Zahniser as important because in his job at the Wilderness Society, he was the primary author and lobbyist behind the 1964 Wilderness Act. This landmark legislation created a nationwide system of lands “untrammeled by man.” My story chronicles a trip Zahniser took in 1947: ten days in Wyoming’s Bighorn Mountains, in what would later become the Cloud Peak Wilderness. It was his first time on a horse.

I came across this story—and a companion story I published this summer about the Bighorn wilderness destination that Zahniser and his friends tried to save—by reading about Zahniser’s life. Mark Harvey’s excellent biography Wilderness Forever has a few pages on the trip. Harvey, like me, relies mainly on Zahniser’s own 1947 account for the Wilderness Society’s newsletter, though Harvey also had access to a personal diary. But because I live near the Bighorns, I wondered if might be able to tell this story with a bit more local color.

Indeed, I found a couple of incredible sources. Transcripts of a government hearing on a proposed dam enlivened this summer’s more political/historical story. Photos and reminiscences from the Schunk family enliven this month’s more personal story. I was also pleased to track down photos at the National Museum of Forest Service History.

These details allowed me to focus on a moment in Zahniser’s life. Harvey and other scholars—including Zahniser’s son Ed—have wisely paid a lot of attention to the summer of 1946, when Zahniser made his first trip into New York’s Adirondack wilderness. It was the first time that this unathletic, partially handicapped man strapped on a backpack. He did so to enter a natural landscape with little overt evidence of modern development. Indeed, the Adirondacks were protected by the New York State Constitution, in ways that clearly shaped Zahniser’s thinking.

But one of the wonders of the wilderness system is the vast scale of apparently-empty lands, mountains stretching off endlessly with little sign of human manipulation. It’s no slight to the Adirondacks or to backpackers to say that most such lower-48 wildernesses are in the West and more frequently accessed by horse. So Zahniser’s wilderness awakening also depended on the following summer of 1947. Although scholars have focused on the weeks he spent living at the Jackson Hole dude ranch owned by his boss Olaus Murie, I found more important the ten uncomfortably rainy days he spent in the Bighorns.

They were important in the sense of shaping the man: his knowledge of the wilderness and the people who loved it, his curiosity, his leadership skills, and the dogged humility of his political philosophy, which shone as brightly in Wyoming as it did in DC.

We often talk about ideas in the form of stories about people. And so it matters which stories we choose. When we tell stories about Zahniser in the Adirondacks, the 1964 Wilderness Act gets implicitly tied to Bob Marshall and the privileged lawyers who wrote those first constitutional protections. When we tell stories about Zahniser supporting David Brower of the Sierra Club in his fight against the Echo Park Dam, the 1964 Act gets tied to Brower, John Muir, and the California-Sierra tradition. When we tell stories about Zahniser’s gigantic tailored raincoat, with pockets for draft bills and brochures and documents to show to the DC insiders he was lobbying, the 1964 Act becomes politics more than nature.

So I wanted to tell a story about Zahniser with beginner’s mind. First time on horseback, surrounded by strangers. Surprised that they wanted to go out in the rain. Eventually awed and humbled by the glory of the natural setting. And forever grateful to the little-known Wyomingites who set him on this path.

Today, threats to wilderness are arguably increasing. In such situations, I think it’s valuable to tell stories. Lots of different stories. Some personal ones—what I did on my wilderness vacation—and some historical ones. With this story, I hope, we see a richer, deeper Zahniser than we might otherwise know. And thus, perhaps, we also see new perspectives and ramifications of his best-known policy achievement.