Advertising wilderness

How advertising shaped the national park system, and whether wilderness needs a market

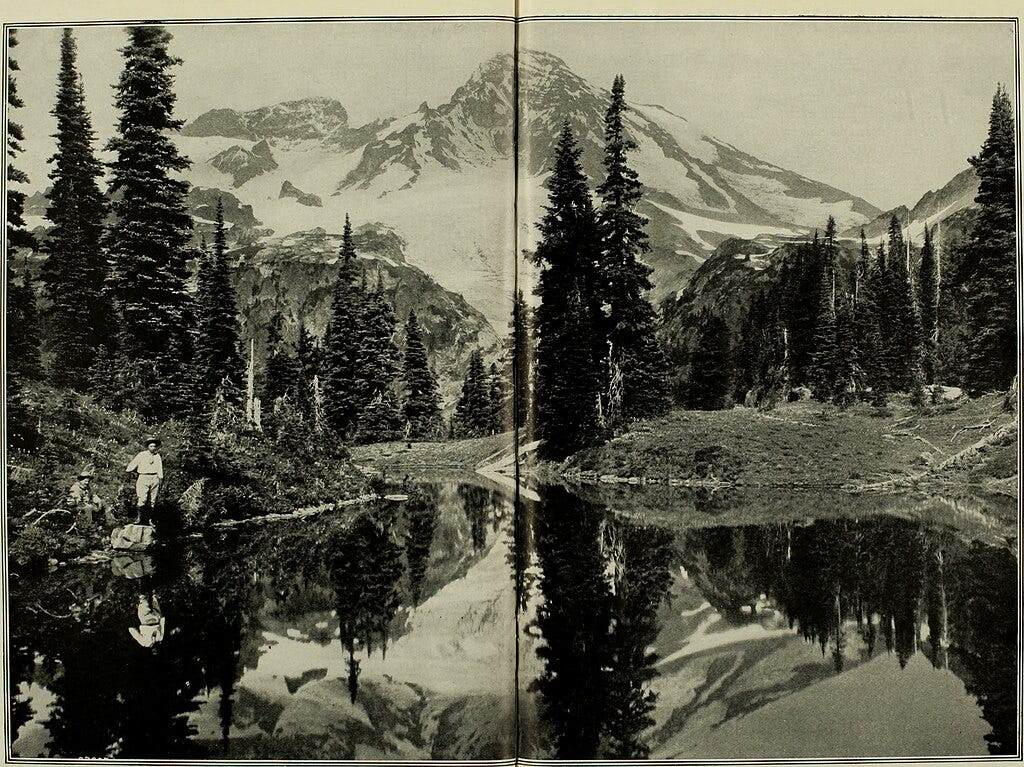

When Steve Mather founded the National Park Service in 1916, he treated it like a start-up. He knew that his job was to hire great people, establish a culture, and build public support. Today we might quibble with some of his choices (too many roads, too much elitism…). But few would look back and oppose the scheme in general. Mather needed to advertise wilderness.

Advertising was essential because public support was essential. Mather needed to get his new agency approved by Congress, and then get the budgets to effectively manage it. Why would Congresspeople from Iowa vote to pay for a park in Wyoming? Only if their constituents saw it as a national treasure. So in 1915 Mather hired his best friend, a former newspaper editor named Robert Sterling Yard, and paid Yard out of his own pocket to run a publicity campaign for the parks.

Mather’s model was his rival agency, the US Forest Service. Fifteen years earlier, its founder Gifford Pinchot had barnstormed the nation on behalf of public lands and forestry. Pinchot gave lectures and interviews. He shaped university forestry programs and foresters’ unions. All while collecting a government paycheck.

In 1918, Congress passed laws to ban much such behavior. For example, a government salary such as Yard’s couldn’t be subsidized from a private source. After all, although most people perceived Mather as principled and selfless, what if he’d been an unscrupulous mogul building a privately-paid team of “federal” employees to pull the newly empowered levers of Progressive government? The system needed to be fair. The government should protect public lands and natural systems, but it shouldn’t be advertising them.

Yet a funny thing happened over the rest of the century: advertising created markets. For example: Mouthwash advertising didn’t merely convince you to buy Scope instead of Listerine, it convinced you that you needed mouthwash in the first place. Yet wilderness and public lands didn’t get advertised—not like televisions and leaf blowers and beauty creams. (Today’s environmental-themed ads are always brought to you by the nonprofit Ad Council, not the government itself.) The general public wasn’t constantly told that it needed wilderness.

This is a common fate for what economists call “public goods.” If public transportation could get advertised like automobiles, it might be more plentiful and better run. If bridge construction could be advertised like subdivisions, we might have more bridges across the river instead of subdivisions on this side of the river. But it’s a tough conundrum to get out of: How could you justify taking a taxpayer’s dollars to advertise to her something that she doesn’t think she wants?

In the case of wilderness, there’s a further implication. Most advertising—the shaping of public opinion—centers on use. Patagonia advertises for public land because it wants you to use its gear to recreate there. (I’m not criticizing Patagonia. Much of its advertising is constructive, even selfless. But in the end, it remains a company that makes money by selling clothing.) Oil companies advertise against wilderness because they want to drill there. Other interests line up at various other use points.

The advertising of wilderness for its own sake—rather than for some use case—is left to advocacy groups. This is hardly unique: you could say the same about farming, or science, or needlepoint. And it may be for the best: who else would we trust to do this advertising? Many of us define wilderness as the opposite of crowds, and thus don’t even want it to be advertised in the first place.

But it does suggest that the “market for nature” is not as big as it otherwise might be. Not as big as its better-advertised competitors.

Should there even be a market for nature? Shouldn’t nature exist outside of markets and capitalism and other flawed human institutions? In other words, shouldn't it be a Garden of Eden?

The Garden-of-Eden approach has come under fire recently because it’s so specific to the Judeo-Christian tradition. It may have worked for the privileged white men of old, but to engage diverse constituencies, we need to… advertise nature differently.

If so, maybe the problematic story hasn’t merely arisen from our attitudes toward the Bible. It’s arisen from our attitudes toward economics, capitalism, and advertising.

Discussion:

I’m inspired here by the ideas of economist Robert Frank, especially as expressed in his 2020 interview with Ezra Klein. Note that Frank’s view of “economics” differs from many popular conceptions.

I previously wrote about Mather here, in the context of nature and capitalism more generally.

I wrote about Pinchot’s use of advertising and publicity in Natural Rivals, pp. 77-78 and 86-91.

A lot to think about here. I think there is a lot of unexplored research that could help conservation groups make a much better case for wilderness for its own sake, and for ours. Potential.

Thanks. We all need to hear from people, whose ideas about economics are not conventional. The indoctrination we recevied in in ECON 101-103 has led us to point where we can't see what's right in front of our eyes.

Re advertising: Iconoclastic economist John Kenneth Galbraith questioned its role 50 years ago, wondering how supply and demand, as popularly conceived and taught, could be useful if the producers were able to stimulate substantial demand via advertising. Didn't that make rational actor economics invalid, or at least suspect? I don't interpet Galbraith to mean that there should be no advertising, but to be directing our attention to the bigger questions (as you do here).

The recent SCOTUS decision validating bribery makes it clear that we are facing powerful people who believe that everything (and everyone) has a price. To them, that is the "natural story." After all they y have a price. Why wouldn't you or I?

How will wilderness fare if they come to power?