What is the opposite of nature?

Actions that helped put nature and capitalism at odds came from an ironic source

In January 1915, Steve Mather, a millionaire businessman who loved wilderness, went to work on its behalf. He took a low-paying position as an assistant to the Secretary of the Interior, in charge of organizing a motley collection of national parks.

Beginning with Yellowstone in 1872, fourteen parks had been commissioned, mostly one-by-one. They were spectacular natural landscapes, often in remote places, that felt special to the nation as a whole. But there was no central vision or program. No goals, no meaningful funding, inconsistent policies. Several parks were overseen by the military, which at the time was the only branch of government with much experience running things. But with a war brewing in Europe, it had other priorities.

Mather’s job was to effectively nationalize the parks: to create a Park Service to oversee them. With his vision, connections, drive, organization, and marketing skill, he turned out to be a brilliant choice. The agency he founded became the most-loved arm of the federal government for the rest of the century. But in his first year on the job, as he toured the jewels under his command, he was appalled at their conditions. Roads were impassable, hotels filthy, staffers unhelpful. Improving operations would take a great deal of management effort.

So Mather made a pragmatic, management-oriented choice: he decided that each park concession—hotels, stores, gas stations—should be a regulated monopoly. He wanted private firms, rather than his agency, to actually pump the gas and change the sheets, because they had more experience at such tasks than did government employees. But Mather wanted to only have to oversee a single firm. That would make it administratively easier to ensure that prices were fair and standards were met. Mather arranged mergers and buyouts to accomplish this goal. He overtly favored the men he liked and could do business with, while pushing out those he didn’t trust.

Mather was principled and selfless, but by today’s standards, he was completely unethical. Railroads and burgeoning automobile associations had far too much influence. Personal whim outweighed formalized competitive bidding processes. At Yosemite, Mather even loaned a concessionaire $200,000 of his personal fortune. His attitudes may have made sense to him, as an individual familiar with running large enterprises. But as a bedrock of longstanding government policy, it was unusual—for one thing, an oddly socialist solution for the titan of capitalism to advocate.

But it worked! Standards improved. Many concessionaires took pride in the park they basically co-managed. Even today, when adventurous people decide to take a summer job “in Yellowstone” or “at the Grand Canyon,” they tend to focus on the place rather than whether their employer is the government or the concessionaire.

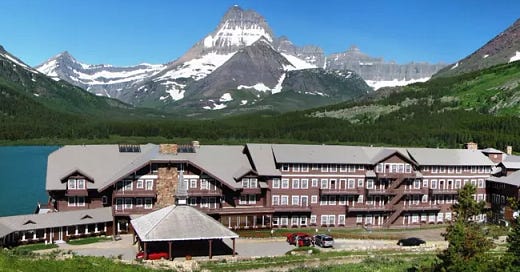

We’ve now had more than a century of these natural monopolies, and I’m fascinated by how they seem to have encouraged a belief that the opposite of nature is capitalism. Obviously nobody wants to insert the profit motive into wildlife management or wildland firefighting. Nobody wants the Many Glacier Hotel to be co-branded as a JW Marriott Resort & Spa, advertised by billboards alongside the Swiftcurrent River. Even when we just want a simple, cheap meal prepared quickly, it would somehow feel wrong to go to a Burger King or Wendy’s inside a national park.

But this puts national parks in a weird category (alongside other government–nature initiatives such as national monuments and wilderness areas). After all, airports are also heavily-trafficked places where the need for standards has led to strict regulation—but not Mather’s monopoly model. Tourist towns such as Sedona, Arizona, seek to protect spectacular vistas through intense regulation of business’ visual presentation—but even though this location has teal rather than golden arches, it’s still a McDonalds.

We might have chosen to define the opposite of nature as development. No hotels or restaurants: in a national park you must camp or picnic. We might have chosen advertising. Or roads. Or manufactured goods such as fleece jackets and comfortable hiking shoes: you leave all your belongings at the border of the national park and instead don a scratchy wool uniform. But we didn’t choose any of those things. We chose a particular form of organizing economic activity. Not the activity itself—you still pay for a hamburger or hotel room—just one form of organizing it.

I’m not complaining! The system has worked well; I’m not clamoring for more competition or profit in natural settings. (I find that people who do so often intend to gain personal profit off taxpayer investment.)

I’m just curious. Natural storytelling is all about conflict. And when nature writers tell stories where the hero is nature or its protectors, who should they choose as an antagonist? Given the state of wilderness in countries with other economic systems, it’s not inherently obvious to me that the answer should be capitalism or capitalists. But this has been the obvious choice for many others, from Steve Mather all the way down.

Perhaps such choices say more about capitalism, or the American practice of it, than they do about nature?

Discussion:

I wrote about Mather here. See also Horace M. Albright and Marian Albright Schenck, Creating the National Park Service: The Missing Years.

In the comments, I’m particularly interested in your thoughts on the title of this post. Maybe, rather than capitalism, something else is the opposite of nature?

Fell asleep thinking about this excellent question.

My answer is that Nature is all there is and there can be no opposite within our experience. We are here, the Parks are here, Stephen Mather had his turn (we found the Mather plate at Carlsbad Caverns when we were there, and at Guadeloupe) as a result of all that has happened since the Big Bang, the dance of the continents, the procession of the great cycles, the proess of evolution. That's what's here and we conscious being are the witnesses or maybe as Alan Watts said, nature's way of experiencing or expressing itself, that we are to Nature what a wave is to the ocean.

The way around this conclusion is to introduce something outside and beyond nature, something supernatural. So, if there were such an entity, which I do not think there is, God would be the opposite of Nature.

One problem with this view is that things like Nazism - which I use as an example because it seems to be the topic de jour on Substack - must be understood as natural. That's hard. But if you understand any form of evil as outside Nature you, as a product of Nature, are unable to do anything about it. You may defeat Hitler, but are still waiting for God to send you something equally arbitary, which believers are taught to hope will be Grace, but could as easily be the 10 plagues all over again.

Sad or not, seeing evil things as part of Nature - as part of natural processes - should give us a sense of agency. The sense of agency that the religious (and in that term I include most of all those who worship money) want to deprive us of so that we may be more easily manipulated.

The problem with that conclusion is that the desire to manipulate others must then be natural (if its not, you have to invent the Devil who is just as unsatisfactory, arbitary, and capricious as God), which means we have to deal with it within or natural capabilities. It might mean, for example, that we have to have our narrative be one of throwing a potlatch rather than investing in stocks and bonds.

That seems like a good place to stop and see what, if anything, others have to say.

I never knew this, how interesting! I’m not sure I’d use the word “capitalism” here, either. It’s a monopoly, heavily controlled, and probably has a limited profit scope. Or at least it’s not free-market capitalism, I guess. Is it the opposite of nature? Or set up as such? What a good question. I’d have to think about it more.