Yellowstone Kelly, natural hero

A semi-famous figure in Montana history, nicknamed “Yellowstone” but not after the TV show... or the park

Luther Kelly achieved fame because of his nerve. He sustained it because of his brains. We remember him now because of his heart.

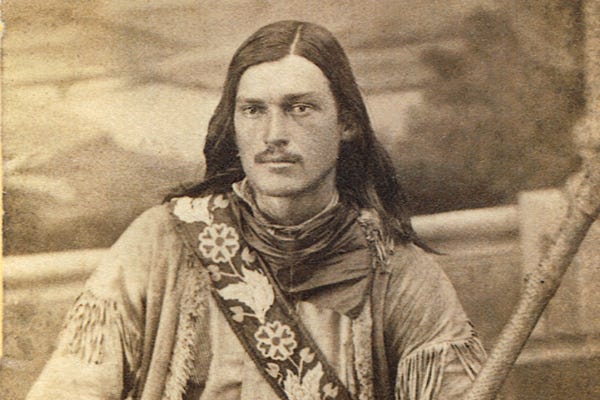

In the 1870s, Kelly wandered the valleys of Montana’s Yellowstone and Musselshell Rivers, and the prairies and island mountain ranges between them. He wore his straight black hair to shoulder length. His nose was prominent, his cheekbones strong. Some called him Sphinx, because he was quiet and shy, bookish for the frontier. The Gros Ventres called him “Little Man with the Strong Heart,” because he’d shown his bravery as a teenaged mail carrier ambushed by Sioux renegades. He eventually became known as “Yellowstone Kelly” for reasons unclear. (The national park was barely established and not very accessible from his region. The TV show was not yet on the air.)

He embodied the romance of a word that was popular then but rarely used today: plainsman. He hunted and trapped. He scouted for the Army. He cut timber to sell to passing steamboats. He poisoned wolves for their pelts—near the Musselshell he once saw 20 of the predators at a single bison carcass.

In the early 20th century, people would nostalgically recall the plainsmen as both natural and free. Kelly always worked for himself, never had a boss. He took risks, having volunteered for that mail-carrier job when no active soldier was willing to do so. Most of the land he traversed was open range, officially owned by the government (“everybody”) rather than an individual homesteader or rancher or railroad (“somebody”) or the Indigenous tribes that had been occupying it for centuries (sadly, in those times known as “nobody”).

In Kelly’s day, the bison on those lands had not yet been extirpated. Elk and other wild animals were still there too—Kelly could feed himself off the land. Indeed, that was the best way to live with these natural systems: to follow the wildlife, rather than being tied to a house and family and garden or farm in such dry landscapes. It was how the Indigenous people had lived here.

Such lifestyles caused a great deal of anxiety in white society. Wasn’t it savage, heathen, or even evil? As evidence, they could point to the habits of white men who favored nature’s ways over society’s ways: drinking, whoring, fighting, thieving, killing.

But Kelly read Shakespeare. His motto, “briskly venture, briskly roam” was a quote from Goethe. He was handsome, literate, and courteous. He didn’t do much gambling, drinking, smoking, or carousing. He thus became known as a man of character—a desirable companion, partner, or employee. A man society could trust.

Americans have always been fascinated by such characters, half natural, half cultured. James Fenimore Cooper’s fictional hero Natty Bumppo loved the wilderness and Indigenous people but served a white culture that he believed was destined to conquer them. Bumppo was a noble, tragic figure precisely because his usefulness to others’ lifestyles directly opposed the lifestyle that he himself loved. Yet he was the ultimate hero of pioneer mythology, his natural story unfolding in natural surroundings.

In the 1880s, as Montana became less wild and free, the real-life Natty Bumppo named Luther Kelly moved on. Colorado, Arizona, Nevada, Alaska, the Philippines. Husband, farmer, soldier, Indian agent, justice of the peace. He had a rich life, but never lost his nostalgia for the plainsmen’s relationship to nature.

Other real-life plains figures, such as Buffalo Bill Cody or Calamity Jane, became legends. But Kelly was never a dime-novel hero. So when he wrote his memoirs at age 79, and had them published by the esteemed Yale University Press, he became famous for being not famous. For being authentic.

So Kelly is now known for this relationship to fame, rather than his relationship to nature. A 1958 movie and 1990s novels used the romantic name to tell rather inauthentic stories. Although Billings, Montana, gave him a grand send-off and special gravesite in 1929, its later efforts to celebrate his legacy have been inconsistent and sometimes poorly received. Yellowstone Kelly has become legendary for not being legendary.

And I can’t help wondering if the problem is the alleged naturalness of the plainsmen’s story. Was Kelly’s method of living off the land really so glorious? Alone, in constant danger and discomfort. Was it really so authentic? When Indigenous people always lived in family groups. Were his contributions to the ascendant white society really so worthwhile? In the moment maybe even he perceived it as betraying his Indigenous contemporaries and the landscapes they all loved.

Maybe he knew his story wasn’t so natural. Maybe everyone did. That’s why his legend emphasized the nostalgic sense of loss—for something that may not have ever existed. That’s why it emphasized the Indian-fighting—which racist tastemakers wanted to believe was natural. And that’s why it seems so foreign to us now, because the landscape couldn’t support it.

Discussion:

For more on Kelly’s life, see Jerry Keenan’s terrific biography Yellowstone Kelly (affiliate link). I previously wrote about Kelly in a paywalled article here.

The Holocaust really happened; Nazis are bad. (I can’t believe I have to say this out loud.) Like many writers on Substack, I’m troubled by its attempt to become a social-media platform without investing in content moderation. Casey Newton explains.

For those particularly interested in the storytelling angles of Natural Stories, you might also check out my friend Allen Jones’ new newsletter Storytelling for Human Beings.

Authentic is a good word.

Interesting read, with good questions and links. Glad to see substack drawing a line.