Who invented wilderness, Aldo Leopold or Arthur Carhart?

Wilderness may be a place, but two Americans present conflicting origin stories for its culture

Yes, the headline is preposterous. Wilderness is a timeless condition of nature’s completeness. It’s not something that a white man invented. But for the last 60 years, American society has sort of treated it this way: we’ve defined wilderness as pristine, “untrammeled” lands behind federal boundaries. We coded it that way in the 1964 Wilderness Act. Howard Zahniser, the author of the Act, never claimed to have invented anything—he was channeling the ideas of others. But whose?

The Wilderness Act enshrined landscapes, but also ideas. Ideas have origins. It’s been something of a parlor game, among conservationists and historians, to track the origination of this particular wilderness idea. After all, we could have defined wilderness differently: to include roads or helicopter landing spots, or to exclude trail maintenance crews or activities such as fishing. Who invented this particular concept of wilderness?

I bring it up because it often comes down to two men, and they have very different natural stories.

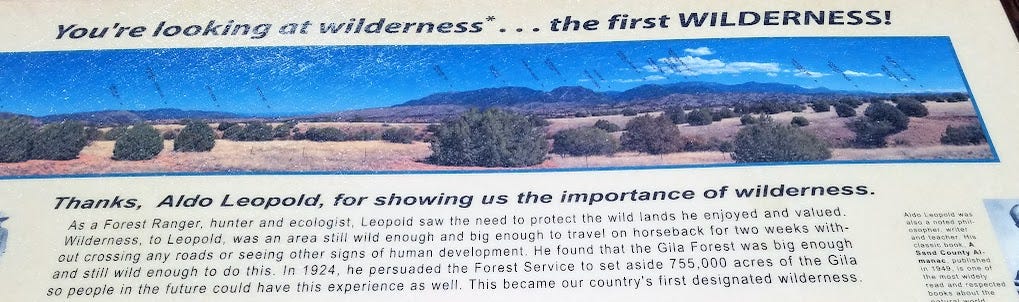

Aldo Leopold is a giant of conservation history. He died shortly before publication of his 1949 masterwork A Sand County Almanac. But he’d started his career at the Forest Service. In 1924 his work led to the administrative set-aside of its first designated wilderness area, the Gila in New Mexico. Later, Leopold co-founded the Wilderness Society, the organization that employed Zahniser to write and lobby for the bill. Most people have wanted to give him credit for wilderness culture.

But in the 1960s, a rival emerged. Arthur Carhart, a semi-retired freelance writer from Colorado, noted that as a Forest Service employee in 1919, he’d been sent to Trappers Lake in western Colorado. His job: to survey the lake for a road and recreational homesites. He did his job, but told his boss that the lake would be better off without the development. The plans were canceled, and Trappers Lake became in effect—if not in formal name—America’s first wilderness. Carhart’s admirers have argued that he, rather than Leopold, deserves credit for first articulating principles of this wilderness culture.

There’s an easy solution: give both men credit. Carhart developed some administrative guidelines, and Leopold was thinking along the same lines. They spent a day talking together in a Denver hotel meeting room; Leopold asked Carhart to write up their notes as a memo. Carhart soon left the Forest Service, but Leopold stuck around and did the hard work to nestle the seed of their idea in a bureaucratic space where it could eventually blossom.

I usually love such uplifting collaborative solutions. But lately I’ve been wondering: in this case, maybe it’s worth emphasizing the conflict. Because it’s not just two different men, two different locations, two different angles on an idea of wilderness. It’s two different stories.

Leopold was shaped by genius and privilege. His father was an industrialist in an Iowa river town. Aldo graduated from Lawrenceville and Yale. He rose quickly through the ranks as an educated forestry leader. His favorite recreation was hunting, especially in old-timey fashion: on foot or horseback, far from the road, deep in country that felt natural and pristine. Like the way it used to feel, on a Teddy Roosevelt frontier. Preserving a scrap of these conditions was what motivated him to set aside the Gila.

Carhart (no relation to the clothier) was a classic middle-class Midwesterner. His father owned a hardware store and then a farm. Although Arthur was trained as a landscape engineer, his first job was installing a rich man’s swimming pool. Then he served in World War I and—craving stability and a sense of public mission—got a lowly government job. He took great pride in having organized a section of National Forest into a sort of park-and-playground for impoverished steelworkers in Pueblo, Colorado. He seemed to most love not a wilderness ecosystem or wilderness philosophy but this idea of using planning and management to steward resources for all.

In the easy solution, these stories merge. Wilderness is a pristine, frontier-like area that is managed to remain untrammeled for the benefit of all. These men are both straight, white, male, cis-gendered college-educated Iowa natives who worked for the Forest Service. They together preserved landscapes and (though they didn’t use this word) ecosystems in examples that Zahniser helped promulgate nationwide.

But today, that merged idea feels endangered. Where do Indigenous people fit in this allegedly pristine frontier? What about other people of color, and women? As human-caused climate change alters wilderness ecosystems, do we still pretend we aren’t trammeling them? And maybe it comes down to: do we manage the wilderness, or not?

So here’s what I’ve been wondering recently: maybe the stories can’t merge. Maybe the differences in philosophy, class, outlook, goals, and attitudes toward management are better held separate.

This doesn’t exactly solve the problem. Each story itself is full of inner conflict. Late in life, Leopold downplayed his past work on the Gila; the wilderness he comes to embrace in A Sand County Almanac is very different from the places that the 1964 Act codified. And Carhart’s plan (thankfully never implemented) for Minnesota’s Boundary Waters, while roadless, involved motorboats and lakeside resorts at a scale that makes him seem more like a power-hungry developer, or a Midwestern Robert Moses, than a wilderness visionary.

But of course these are the issues we still face today. Is wilderness the opposite of technology, of comfort, of progress? Is it some allegedly pristine place behind a faraway boundary? Is it an intact ecosystem or an intact state of mind? (Whose mind?)

These are tough questions, I don’t know that anyone can answer them right away. To me the urgent issue is: Might the path to those answers come from disentangling the stories of who invented wilderness? And if we say yes, then what happens?

Discussion:

Welcome to the many new subscribers this week! You can always comment on these stories or peruse the archives. This post is public, so please feel free to share.

A gold standard of biographies is Curt Meine’s Aldo Leopold. Two Carhart biographies are Tom Wolf’s Arthur Carhart: Wilderness Prophet and Donald Baldwin’s The Quiet Revolution: Grass Roots of Today's Wilderness Preservation Movement. Paul Sutter’s Driven Wild addresses both men. (These are all affiliate links.)

Sometimes I offer a prompt for comments. In this case, the essay’s conclusion serves that purpose.

Does it help hold the threads of the story separate if we say that Wilderness evolved, rather than being invented? It is, after all, an institution, not the proverbial "wheel" that we're not supposed to re-invent. And as you suggest, it continues to evolve..