Thomas Wolfe and the greatest Western novel that never was

Reflections on the role of story in reflecting and shaping culture

Does a great work of literature primarily reflect culture, or shape it? It’s easy to argue that a writer exists within a culture and reflects its values. On the other hand, especially if you’re a writer, it’s easy to hope that you have created or reported on a world in ways that will cause readers to take action. You want influence.

I’ve long thought that the history of the American West demonstrated that influence. The settler-colonial culture is so new that we can watch culture being shaped—and literature doing the work. For example, consider Owen Wister’s The Virginian, which set the template for every cowboy novel and movie created since, and thus a great deal of how Western men see themselves. Or consider Laura Ingalls Wilder’s depictions of homesteading in the Little House on the Prairie books—equally rife with mythology that’s had an equally lasting impact.

Seeing the West from afar, from books and movies, I almost assumed that I would have to center a life here on riding horses, carrying six-guns, and/or taking up a homestead to prove myself to the schoolmarm. Only after I arrived, 34 years ago, did I realize that these actions were more symbolic than literal—they were just the novelists’ influence.

Meanwhile, I’d grown up in a region under the influence of New England writers such as Emerson, Thoreau, and Hawthorne. I felt constricted by their dour, over-intellectualized sermonizing. Yet Florida seemed to belong to Carl Hiaasen and Jimmy Buffett; Los Angeles to Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald. Literature shaped each region.

Why? Because we end up not just reading our favorite books, but also trying to live them. Of course it works with other media too, as fans of the “Yellowstone” TV show seem intent on proving.

In short, this idea of writers and artists influencing regional culture felt as solid as any belief I could have. But my encounter with Thomas Wolfe changed it.

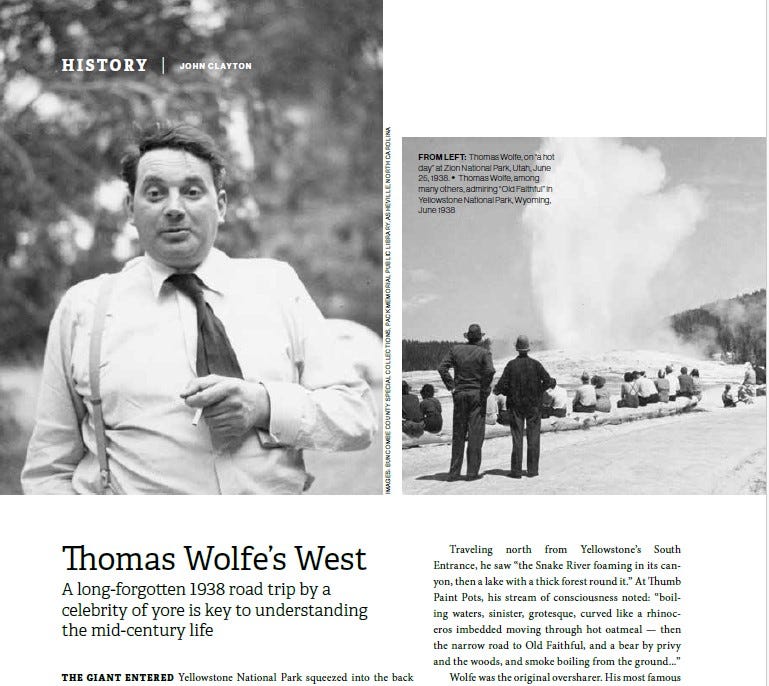

This month I’m publishing a major new article on Wolfe, in Big Sky Journal. You can read it free online here, although I highly recommend the printed version with its gorgeous layout. Keep in mind that I’m not talking about the white-suited New Journalist and novelist Tom Wolfe, active from the 1960s through the 2000s. Instead it’s the stream-of-consciousness novelist Thomas Wolfe, active in the 1920s and ‘30s, the one who said “You can’t go home again.”

As if to prove it, in 1938 he took a whirlwind auto tour of the American West. He was a prodigious and appreciative traveler. For example, in You Can’t Go Home Again, he wrote, “Perhaps this is our strange and haunting paradox here in America — that we are fixed and certain only when we are in movement.”

Wolfe scribbled notes during his whole Western trip, intending to turn these experiences into a Big Novel. He was already, in his mid-30s, a famous Big Novelist, having scribbled through his lives in Asheville, North Carolina, and New York City. He was a celebrity, and controversial—Hemingway and Faulkner sharply disagreed about his talent.

So this trip fostered anticipation: how would he fare writing about the West?

That anticipation is the subject of my story. Spoiler alert: Wolfe died before he could write his Western novel. But as I researched my story, I realized that if he had written it, we would see it as influential. Wolfe’s notes indicate that he was interested in themes that ended up defining the West: national parks, automobile tourism, provincialism, and a tension of cultural progress.

Wolfe was drawn to the fertile landscapes of Mormon Utah, while simultaneously horrified by their conformity. Meanwhile, he was drawn to transient communities in national parks, but knew that the relationships tourists forged there—with other people and with nature—were superficial. Through the rest of the 20th century, attendance at both national parks and LDS churches grew rapidly, and indeed came to dominate national ideas of the culture of, say, Utah.

Wolfe’s notes have these tensions butting up against each other. He seems to be asking: Which is the better way to live in the West? Living by the land in a verdant Garden of Eden that allows no individuality? Or as a footloose individual dancing all night with strangers far from home? Which is the natural story?

These questions struck me as similar to the conflict that Wallace Stegner identified as driving Western history, between stickers and boomers. Stegner identified the conflict in 1992, when his essay reflected on a culture. Wolfe was pursuing that conflict in the 1930s, when it was newer, or at least not yet well articulated.

Thus, if Wolfe had carried his themes through to a novel, and if the novel had been good—granted, those are two big ifs—we would look back on his novel as having defined the culture of the post-WWII rural West. We’d look back at Wolfe the same way we do Wister, Wilder, and Chandler. We’d see Wolfe as having written, or discovered, some sort of guiding natural story.

And yet we know for sure that he didn’t influence the West. Because all he did was take a whirlwind vacation here, just like millions of other people. His notes suggest that he might have done more. But I am now forced to conclude that it would have reflected an existing culture, rather than shaping a future one.

Discussion:

For more on Wolfe, see Anne Trubek, “Fading From View,” Daniel Barth, “Thomas Wolfe's Western Journeys,” and Edward M. Miller, “Fortnight’s low-cost trip takes in western parks,” The Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington) Sun, Jul 31, 1938, Page 71.

For more on Stegner, I’m amid Philip Fradkin’s Wallace Stegner and the American West and am eager to read the collection Wallace Stegner's Unsettled Country: Ruin, Realism, and Possibility in the American West.

Hey, John. Neat piece. I must admit: I knew much more about Tom than Thomas. Thank you.

As a guy who wrote a road-tripish novel, set in the late '60s (Boston-->Nebraska-->Montana-->Alaska; bit.ly/CWS-e) I'd be curious as to how (or if) you see Thomas Wolfe's work touching the rootless-weird Kerouac of the 1950s who influenced Hunter S. Thompson's 'gonzo' road-trip stuff in the '60s and '70s. Not Stegner's cup-o-tea (or mine--anymore) but they seem at least tangentially connected. Thots?