Theodore Roosevelt, the most overrated celebrity in Yellowstone history

Roosevelt shaped the elite hunter-conservationist tradition. But is that what Yellowstone National Park is really about?

Three days south of Yellowstone’s Heart Lake, the storm blew in. Although it was only September, the wind was cutting and the rain icy. The party kept moving. They were two hunters, two guides, a packer-cook, a choreboy, and 20 horses. Finally “the storm lulled,” one of the hunters wrote, “and pale, watery sunshine gleamed through the rifts in the low scudding clouds. At last our horses stood on the brink of a bold cliff. Deep down beneath our feet lay the wild and lonely valley of Two-Ocean Pass.”

It was 1891, and the hunter’s name was Theodore Roosevelt. This was his first visit to greater Yellowstone, a place that would loom large in his legacy. “There is no more beautiful game country in the United States,” Roosevelt wrote, and “This was one of the pleasantest hunts I ever made.” He enjoyed the comfort of a full pack train, the skills of the guides, and the ease of well-worn elk trails. He encountered few other people, just the family of hunter-trapper Richard “Beaver Dick” Leigh. Amid the storm, Roosevelt killed an elk and cut off its head for a trophy, though he left most of the meat behind.

His experience was uncommon—few people could afford to travel in such luxury—but typical for white male hunters of his class and time. The frontier and the West meant many different things to many different people. But to Roosevelt and his fellow hunter-conservationists in the Boone and Crockett Club, it had the wildlife, scenery, and physical challenges to make a perfect experience.

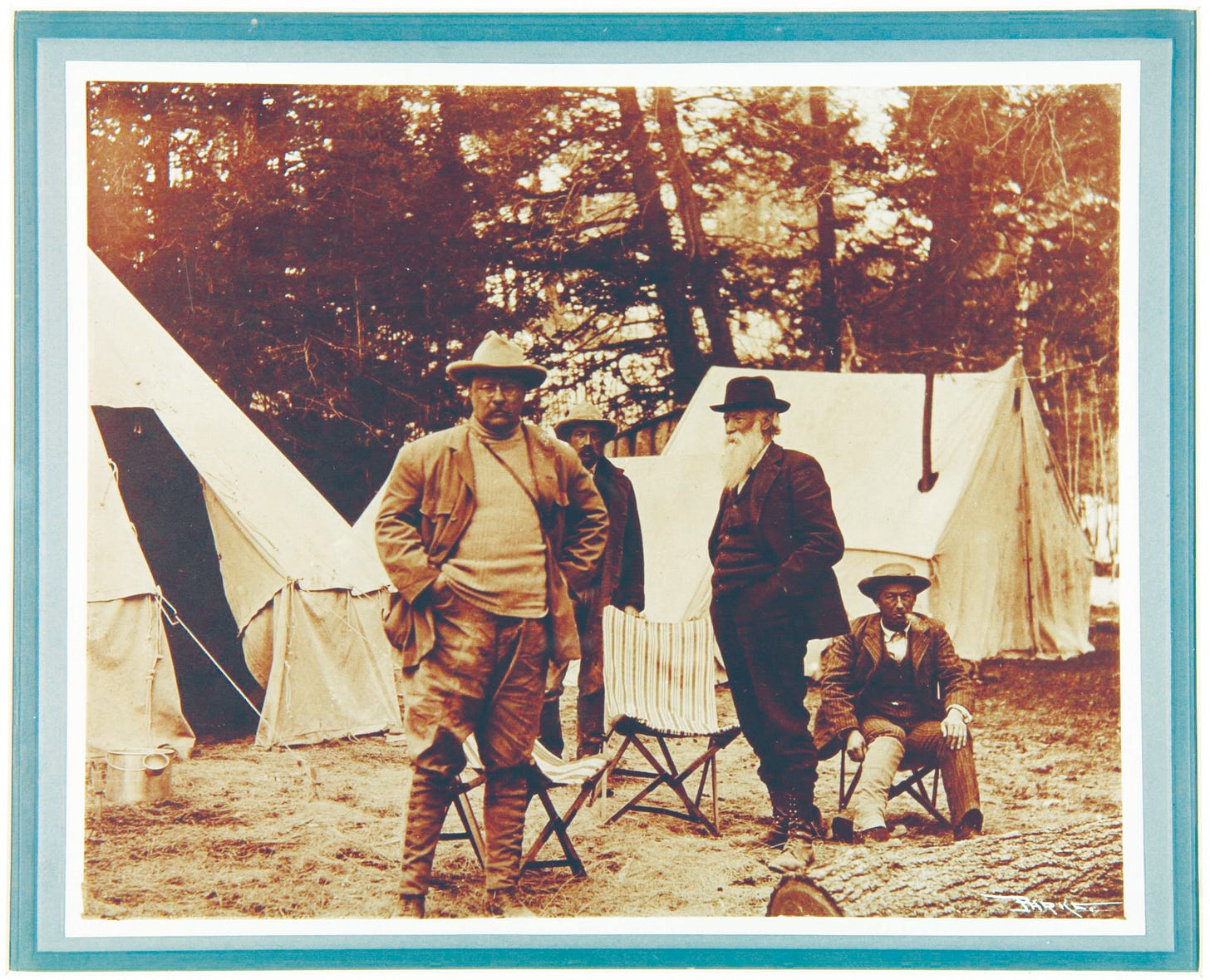

A trip from 122 years ago this month forever linked Roosevelt’s name to the park. In April 1903, as President, he spent two weeks camping near Tower Falls with naturalist John Burroughs. He called Burroughs—a prolific writer twenty years his elder—Oom John, a Dutch word for uncle. At one point Roosevelt came out of his tent with half his face shaved, the other half still full of lather. Some mountain sheep were coming down a cliff face. “By Jove, I must see that,” he said. “The shaving can wait, and the sheep won’t.”

While they were in Yellowstone, the Park began construction of a new arched entrance at Gardiner, Montana. Administrators asked Roosevelt to lay the cornerstone and give a speech, which has since been much quoted.

And that’s about it. That’s the extent of Roosevelt’s direct influence on the world’s first national park.

In Wonderlandscape, I wrote that Roosevelt was “Yellowstone’s Most Overrated Celebrity.” The arch is now named after him, as is a 1920 rustic-styled lodge near where he and Burroughs camped. He’s perceived as such an important figure in the history of conservation that people figure he must have been important here. But he played no role in establishing the park or influencing its policies, aside from supporting some advocacy by other leaders of the Boone and Crockett Club.

I always expected more pushback on my claim. Roosevelt fans are legion. I almost hoped that one of them would publicly attack me, so that we could ride the controversy to bestsellerdom. But I make a poor controversialist. After a few paragraphs, Wonderlandscape tempered the “overrated” theme. I admitted that Roosevelt was indeed important, if not to Yellowstone then to the America that consecrated it.

Roosevelt expanded the national park-and-monument system, set aside 230 million acres of land from development, formalized the Forest Service, and most importantly embraced outdoorsmanship. Just the idea of interrupting your Presidency to take a two-week camping trip was a substantial use of the bully pulpit. Between his policies and his personality, Roosevelt became a sort of patron saint of conservation.

Roosevelt believed that the “English-speaking race” was superior to others. He had plenty of macho bluster, and plenty of non-white-males were victimized by it. Indeed, in the seven years since I published Wonderlandscape, many of Roosevelt’s contemporaries in the conservation movement have been condemned for their belief in the racist pseudo-science of eugenics, for their use of racially insensitive language, and for actions suggesting a belief in white racial superiority. In my opinion, Roosevelt’s sins in these areas were greater than those of, say, John Muir or Gifford Pinchot.

There’s a powerful counterargument: we can’t judge historical figures by today’s standards, when such attitudes were sadly common to their times. Anytime we seek to judge rather than understand, it gets confusing. For example, how do we judge John Burroughs? He had admirable attitudes toward nature, but, at the time of his Yellowstone sojourn with Roosevelt, was unhappily married, sexually voracious, and having an affair with a much younger woman. By the standards of their own times, his may have been the less moral life.

Rather than judge Burroughs or Roosevelt, we can see them as celebrities embodying the values of their time. Like the Hawk Tuah Girl rising to fame for her talents at social media, personal branding, and cryptocurrency, Roosevelt’s fame came from talents that epitomized the hunter-conservationist movement. That movement saved species from extinction and helped America embrace the value of wildlife habitat.

But a 1920s proposal to build a big Yellowstone museum, with busts of scientists and explorers—and Roosevelt at its emotional heart—went nowhere. The problem: why would you build an indoor structure honoring elite hunter-conservationists amid a place where middle-class family experiences of outdoor wonders far outstripped that old vision?

In other words, there was no need, back then, for judgements about Roosevelt’s racism or classism or sexism or hunting practices or political compromises or pseudoscientific curiosities or anything else. He was already Yellowstone’s most overrated celebrity because the values he embodied were already, not long after his 1919 death, an overrated match for this setting.

Discussion:

I’ve quoted Roosevelt from his 1893 book The Wilderness Hunter (Hathitrust edition) and from John Burroughs’ Camping & Tramping with Roosevelt (Gutenberg edition). For context, see also Richard A. Bartlett, Yellowstone: A Wilderness Besieged, especially pages 60-61.

For another look at judging historical figures by today’s standards, see my 2020 blog post “Was John Muir Racist?”

I get a slight commission when you click on affiliate book links, but I’m just as happy if you buy from a local independent bookseller.

I am so envious of TR’s 1891 trip into that country that i have no other comment.

Good read. Roosevelt was definitely a mixed bag. He was a war-monger and created Panama so we could have a canal, but he also did some good things. Would have been an interesting guy to meet. (PS: nice that your affiliate also supports local bookshops, as opposed to that other place.)