The visionary farmer who replaced nature with industry

A natural history of Thomas Campbell, who built America’s biggest wheat farm

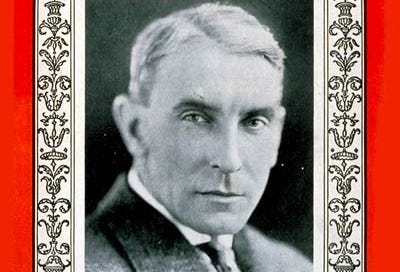

When Time Magazine put Tom Campbell’s picture on its cover, on Jan. 9, 1928, it profiled his wheat farm outside of Hardin, Montana, which it called the biggest in the country. Campbell was a visionary who’d seen the future of farming. Unless—

Maybe the reason nobody has heard of him today is that he was wrong.

Born in North Dakota in 1882, Thomas D. Campbell grew up with an intimate understanding the disadvantages of wheat farms that were dependent on the labor of horses and humans. The solution, he decided, was to apply intensive machinery and efficient management to large-scale operations. A World War I food crisis (how would we feed the doughboys?) gave him an opportunity. He convinced the federal government to help him arrange a favorable long-term lease for huge expanses of Montana’s Crow Indian Reservation—and convinced J.P. Morgan, Jr., and other financiers to give him two million dollars in funding.

Campbell had an innovative theory. Most previous farmers had believed that the land, the people, or their horses were the factors that could limit a farm. Campbell said that instead it was the tractor. He spent Morgan’s money on huge, sophisticated tractors—and then altered all of his farm operations to suit the tractors. In other words, he wasn’t merely ahead of the curve in understanding how to use motorized equipment on farms. He was also ahead of the curve in adjusting structures and systems to the new technologically-dictated realities. For example, he considered his advances in the windrow method of harvesting to be one of his major contributions to industrial agriculture.

It wasn’t that Campbell valued machines more than people. He was a brilliant manager who paid his employees well. It’s that he valued machines more than any feature of an old-fashioned farm that might reduce the machines’ efficiency: an awkward turning radius, an unexpected dip, small-scale ownership, a tree.

In 1948, Campbell harvested a record half a million bushels of wheat, worth $1.5 million. The following year, big-hearted Montana journalist-historian Joseph Kinsey Howard looked across the Campbell Farming Company’s 28 miles of wheat, a golden basin backed by a blue-shadowed mountain ridge, and declared it “one of America’s most spectacular vistas.”

The book on the Campbell Farming Company is titled Every Farm a Factory. That title nicely captures both the glory of Campbell’s dream and the revulsion many people have to it. Imagine if every farm was a factory—we could feed the world as efficiently as we provide it with plastic trinkets, and nobody would ever starve to death. Yet why on earth would anyone want to turn a farm, that glory of the natural world, into the soul-deadening hell known as a factory?

In addition to industrial vision, Campbell had public-relations genius. He managed to get magazine coverage of his most profitable years, and silence about his poor ones. Drought and logistical problems—especially machinery breakdowns—resulted in the loss of almost all his financiers’ money. And it’s telling that he kept pursuing leases on Indian reservations, where the federal government could make sweeping decisions that ignored or suppressed the views of the people who were closest to the land.

Yet we can’t dismiss Campbell as a greedy capitalist. Indeed, some of his greatest successes came in the Soviet Union. In the 1930s, Josef Stalin had the landholding scale and proletarian-industrial vision to implement Campbell’s ideas. Alas, Campbell found that the Soviets were even worse than the Americans when it came to providing him with reliable machinery.

Rather than political ideologies, what Campbell most loved was the application of technology. And thus it’s tempting to portray him as an enemy of nature. Because we tend to see nature and wilderness as the opposite of technology.

Except, of course, when we don’t.

In 2017, Pat Brown, the founder and CEO of Impossible Foods, called meat production a “technology problem.” He suggested that his animal-free production of hamburgers—like Campbell’s horse-free production of wheat—would productively transform agriculture, society, and nature.

It’s the same question: Where are the lines between nature, agriculture, and technology? And where should we stake our moral positions?

Maybe Brown and Campbell are right, and humans are separate from nature, and our hamburgers and buns should be as industrial and non-natural as possible. Maybe they’re wrong, and I should enjoy this locally-harvested meat, this apple off the tree, this honey from my neighbor’s bees.

I don’t really know. But what deeply puzzles me is how often we all try to act as if Brown and Campbell are both completely right and both completely wrong simultaneously.

Discussion:

Deborah Fitzgerald’s Every Farm a Factory: The Industrial Ideal in American Agriculture is a thorough academic study. Joseph Kinsey Howard’s 1949 Harper’s Magazine article “Tom Campbell: Farmer of Two Continents” is typically readable. The Montana Historical Society has collections of clippings, papers, and old films.

I have long been fascinated by Campbell and hope someday to write about him at greater length.

This essay glances on some controversial topics, and I trust that y’all will be typically respectful in the comments. Thanks!

I love this story, although I don't know much about Campbell beyond what Joe Howard wrote. My sense is that Howard thought this was a left-leaning communal alternative for agriculture, that it belongs in the populist left experiments of the 30's seeking alternatives to individual capitalist farming. Any truth in this? Also, is there any significance to choosing land on the Crow res? Cheaper to lease, or something else going on? Finally, what has happened to all of this land today? And where is it? Might be worth a drive.... Thanks for the great story.

Ideally, people would know the origin and carbon footprint of everything they eat. Most have no clue. And one of the things America can be least proud of is drive-through fast food. Talk about industrial and unnatural.