The end of wilderness solitude

In Part 3 of the Solitude Trilogy, maybe we’re all living in Edward Abbey’s world—and maybe that’s not a good thing

In Part 1, I failed at wilderness solitude. Part 2 showed how wilderness and solitude got married. Today: can (should) this marriage be saved?

In his compelling cover story for the February Atlantic magazine, Derek Thompson writes about our “century of solitude.” His thesis: “self-imposed solitude might just be the most important social fact of the 21st century in America.” Solitude, Thompson says, is “rewiring American identity.” It’s a fascinating, thorough story, and—especially relevant to nature-lovers—it never mentions wilderness.

Over the past few years, as I’ve been trying to write a book about the history of wilderness, I’ve come to appreciate wilderness advocates’ solitude argument. Ecological arguments for wilderness quickly get tangled up in managing for climate change, spiritual arguments in discomfort about Judeo-Christian mythology, and historical arguments in race, class, and imperialism. But opportunities for solitude—who can disagree? Surely everyone sees a need for solitude, and wilderness provides opportunities to pursue it.

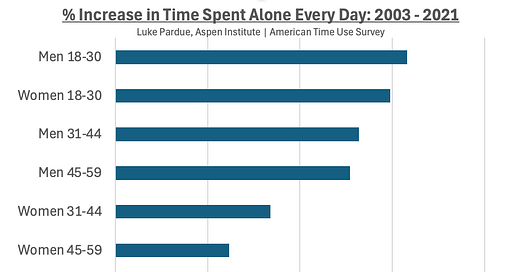

Yet Thompson points out that Americans now, overwhelmingly, choose to get our solitude from other sources. In-person socializing is declining; 74 percent of all restaurant traffic is takeout or delivery; leisure time is increasingly spent watching TV or staring at the phone rather than interacting with people at a tavern, church, movie theater, or bowling league.

The causes are not surprising: Most importantly, the rise of television, the Internet, and the smartphone. Also, the increasing size and comfort of people’s homes, and the increasing hassles and risks of leaving them. Plus the increasing availability of DoorDash and Amazon and Netflix and work-from-home options. These advances have improved many people’s lives, including my own. But if you think of these advances as an increase in collective wealth, it’s interesting what we choose to spend it on—solitude.

If, as I argued last week, wilderness visitors are seeking to get away from other people, then the problem of the wilderness is that there are much more convenient ways to achieve that goal. Obviously that’s not the whole picture of wilderness—you gain not only an absence of people, but also a presence of trees, rivers, mountains, and creatures. You gain everything implied by the ecological, spiritual, and historical arguments for wilderness. But the point is that—I am disappointed to realize—the solitude argument for wilderness turns out to be just as tangled as all the other arguments.

After all, one of Thompson’s most fascinating discussions is with psychologist Nicholas Epley, author of a paper titled “Mistakenly seeking solitude.” Epley says that we always think we will enjoy solitude more than we actually do. We underestimate the benefits of connecting with others; we would (all of us, even self-described introverts) be happier if we spent less time alone. And so one has to wonder: is it really in our self-interest to crave wilderness solitude?

One of Thompson’s most troubling discussions addresses how solitude affects politics. Time alone, he says, makes society “weaker, meaner, and more delusional.” Home-based, phone-based culture may strengthen our closest ties (family) and affinity ties (fans of the Red Sox… or of wilderness), but it decimates a middle ring of people we used to be forced to encounter. A neighborhood, a village. When we had to interact with such people in person, we needed to find compromise about any political disagreements. Now that we can ignore those people, or encounter them only online, we can see them as demons or aliens.

Thompson explicitly cites folks today on both the right and left. But I also thought of Edward Abbey. Arguably the patron saint of wilderness solitude, Abbey often took jobs as a remote Forest Service fire lookout so that he could spend a summer in wilderness solitude. (The fact that he claimed to be solo but often had female companionship says more about the American individualist tradition than it does about solitude.) Abbey then wrote books like Desert Solitaire to demonstrate the primacy of the solitude he found in wilderness.

Yet in dozens of late-life screeds, Abbey infuriated many supporters by belligerently opposing feminism, immigration, and gun control. His fans have since struggled to reconcile his beautiful writing and environmental philosophy with the ugly contempt of his politics. Thompson’s arguments explain it: Abbey’s politics—his ideas of how to interact with people who disagreed with him—were warped by too much solitude.

Abbey famously said, “The idea of wilderness needs no defense, only more defenders.” The quote has never made sense to me: How would you attract more defenders to any idea without making a defense of it? How would you build an inclusionary politics behind wilderness without talking about the ecology or the spirituality or the history or the solitude?

And now I sadly understand. Solitude made Abbey weaker, meaner, and more delusional. Solitude caused Abbey to see his opinions as self-evident, and people who disagreed with them as demons or aliens. Solitude may have polished him into an idealized version of himself—and maybe, in some big picture, that was worthwhile. But in other ways, Abbey’s solitude ended up degrading the idealized wilderness he so wanted us to love.

I began this trilogy by saying that on my first solo backpacking trip, I failed at wilderness solitude. In an early draft, I wondered if I had failed wilderness solitude—in other words, if my character flaws didn’t live up to this ideal. I then realized that the ideal has its own failures (as all ideals do). I didn’t fail it, it didn’t fail me—but failures happen, and for wilderness to thrive despite them, wilderness lovers may need to struggle with these questions… together.

Discussion:

Thank you to my paying subscribers! Your subscription makes it possible for me to write stories like this and publish them for all to read.

So why does one go out there alone? I cannot speak for Abbey or Thoreau or other advocates of “solitude,” but I spent many days roaming alone when I was younger and upon reflection, it was not to get away from other people. But that doesn’t mean the solitude wasn’t important.

It sounds awkward, but as near as I can tell, I went out there by myself to get away from myself. The absence of other people was a prerequisite to that at that time in my life. The wild was a nonhuman presence (sometimes embodied in an elk or a bear or even a camp robber) powerful enough to get me past my own petty, anxious self, to call me to expand and connect.

I don’t know though that what I was doing was spiritual. Maybe? It wasn’t recreational by any definition. So had you asked me, think I might have said I was seeking solitude. Defining these values is not easy

There are proven health benefits to spending time in nature and for time without the buzz and, dare I say it, chaos, of "civilization." That says something about an innate and physiological need for some elements of nature and solitude in our lives.