Rudyard Kipling’s racist wilderness vision

What if we saw Kipling, rather than John Muir, as the chief prophet of the American wilderness ideal? How might that change our outlook on wilderness and race?

In June of 1889, the master-of-narrative Rudyard Kipling visited Portland, Oregon. He wrote to a friend, "Portland is composed of three streets—two very dirty and one not at all clean." He then took a steamboat ride up the Columbia River to The Dalles, and back the next day.

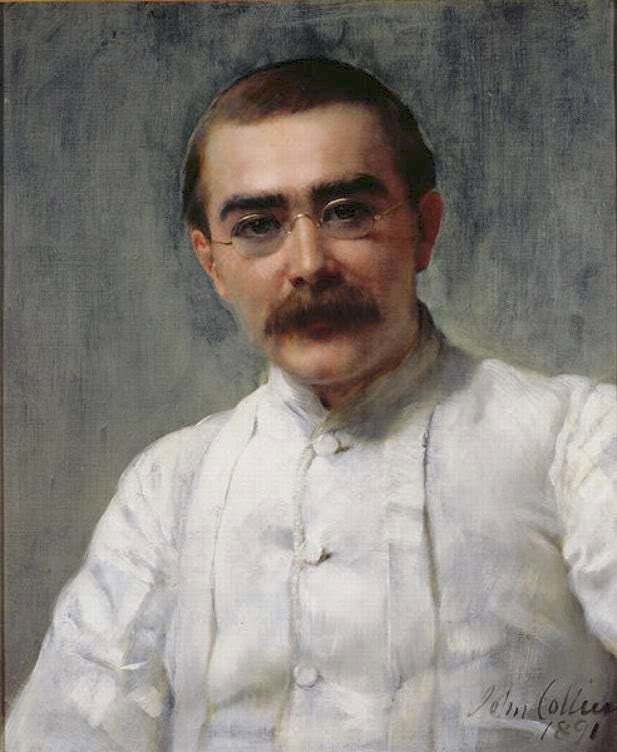

Kipling, at age 23, had already published hundreds of short stories, some of them brilliant. He’d written most of them from India, and was now on a round-the-world journey to London. He paid his way by writing articles for various publications. In one of them, he described his astonishment at a scene on the Columbia, as his steamer stopped “to pick up a night's catch of one of the salmon wheels on the river” for delivery to a cannery downstream.

The catch was 2,230 pounds of fish. Thinking that number an exaggeration, Kipling wrote, “I counted the salmon by the hundred—huge fifty-pounders hardly dead, scores of twenty and thirty pounders, and a host of smaller fish.”

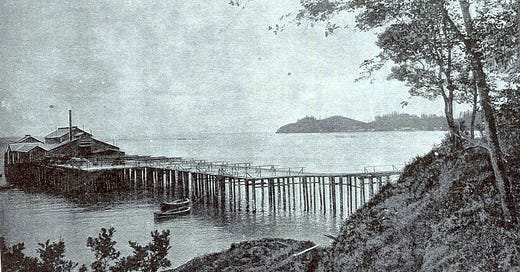

Then they steamed down to the cannery, and he was even more astonished. “The crazy building was quivering with the machinery on its floors.” It produced 240 cans of fish meat in just the twenty minutes he watched. Yet “I was impressed not so much with the speed of the manufacture as the character of the factory. Inside, on a floor ninety by forty, the most civilized and murderous of machinery. Outside, three footsteps, the thick-growing pines and the immense solitude of the hills.”

Kipling’s racism makes him a problematic figure today. And make no doubt, he was racist. His account lingers on the cannery’s employees: “Only Chinamen were employed on the work, and they looked like blood-besmeared yellow devils as they crossed the rifts of sunlight that lay upon the floor… Chinamen, with yellow, crooked fingers, jammed the stuff into the cans.” It must have been miserable, essential work, yet Kipling could not see the people or their stories. He found the machinery far more worthy of attention.

Yet the reason that people today pay attention to Kipling, despite his racism, is that he so effortlessly captured the values of his times. Most of the people who purchased his bestselling books were, sadly, caught in a fully racist culture. They were also, justifiably, fascinated and concerned with this machinery, this industry, that was coming to reshape their world. Kipling captured their views with uncanny insight, bracing clarity, and narrative style.

Take, for example, his inside/outside contrast: murderous machinery versus hills, pines, and solitude. “For Kipling,” writes historian Richard White, “the canneries encapsulated a basic spatial division between the mechanical and the natural. Inside, crowding, humanity, death, machines, routinization; outside, solitude, nature, life, the organic, and freedom.”

Ever since Kipling wrote it down, Americans have utterly embraced this division. Nature and wilderness are the opposite of industry, of murderous machinery. For example, the 1964 Wilderness Act prohibited “motorized and mechanical access.” It is not humans that are the problem (you can visit a wilderness), nor our tools (you can bring packhorses and fleece jackets), but our industry. Like Kipling, we are astonished at the speed and power of machinery, but even more concerned about its character. Could it ruin the rest of nature the way those canneries were ruining the salmon runs? We want to wall off the factory to protect the pines and hills. This concern is justified: factories are relatively new in human history, and breathtakingly powerful to anyone who tours one.

In addition to the spatial division, White writes, Kipling “asserted a temporal division. Mechanization was the mark of the modern, nature was a primordial past.” Some of my environmental friends like to point out that “conservation” and “conservative” have the same root (their point being that Republicans should support conservationist causes). And here we see it in action: factories are new, factories are dangerous, let’s hold off on embracing this change until we have a better sense of its costs.

Finally, Kipling also asserted a racial division. “Only Chinamen were employed” at the canneries. In retrospect it seems clear that, due to racism, these were the only jobs they could get. It was white capitalists who owned the factories, and reaped the profits of the horrifically large-scale slaughter of salmon, accomplished in conditions that endangered their impoverished employees. Kipling didn’t mention the factory owners, instead describing “the slippery, blood-stained, scale-spangled, oily floors and the offal-smeared Chinamen.”

Kipling wrote, “I dropped a tear over them.” But “them” referred to the salmon, “monarchs who deserved a better fate.”

He was deeply affected by the sight of the huge quantities of dead Chinook (“king”) salmon. As the boat ride continued, “We talked fish and forgot the mountain scenery that had so moved us a day before.” To recover, he then sought a genuine, intimate, personal interaction with nature. After returning to Portland, he arranged a trip up the Clackamas River. His friend hired a team of horses. Kipling wrote, “The team was purely American—that is to say, almost human in its intelligence and docility.”

Most of Kipling’s article was about the Clackamas rather than the Columbia. It was a classic fishing trip: the glories of America’s natural landscapes restored his soul. Kipling perceived it as an individualized, low-tech interaction with nature. He mentioned twice that his rod weighed only eight ounces. He was proud of the various Chinook salmon for fighting him in episodes lasting up to 37 minutes. And he was proud of his pals for keeping only three of the sixteen fish they caught, releasing the rest after weighing them to demonstrate their nobility.

Knowing Kipling’s affection for masculine stories of colonial conquest, it’s hard not to see the fishing trip in that vein. The American wilderness, like that of India, was merely a setting for elites to prove their character. A natural monarch, like the Chinook salmon or Kipling himself, deserved the honor of a one-on-one, minimally mechanized battle for survival. The factories only degraded Kipling’s, and the Chinook’s, opportunities for individual triumph.

In 2020, the Sierra Club denounced its founder, John Muir, as a racist. The response from many people—including me and, more importantly, members of the Sierra Club’s own board of directors—was basically, “Oh no! Don’t cancel John Muir!” He was such a gentle and playful soul, so opposite the greedy colonialist, that it seemed unfair to point out the occasions when he had carelessly echoed the overwhelming racism of his times. Yes, he occasionally referred to Blacks or Indigenous people with words that today we recognize as horrific slurs… but we want to give this guy a break.

With Kipling, we’re less likely to want to give him a break. His racism has long been established, its effects long debated. Perhaps because these debates happened long ago, today few worry about “canceling” Kipling. Instead we seek understanding of how, despite some incredible gifts, he could so vividly represent a set of deeply colonial, racist values that our society would now like to overcome.

If we accept all this about Kipling, an interesting question arises: Is Muir or Kipling more responsible for the American wilderness vision of today? There are good arguments against Kipling’s relevance: He was British. His 1889 American journey was only a few months, with only a few days in natural settings. He never claimed that his oft-sarcastic articles, later collected in the book American Notes, were anything more than superficial first impressions. Furthermore, that book uses the word wilderness only once—in reference to downtown Chicago.

On the other hand, the book was published in 1891, before most of Muir’s books. In 1892 Kipling married an American woman, and lived the next four years in Vermont. That same year The Century magazine (at the time America’s finest) offered him the largest price ever paid for a short story.

The magazine’s associate editor, Robert Underwood Johnson, was impressed with Kipling as soon as they met. Kipling, he wrote, had “the strong conviction of a thinker, whose every look at this shifting world is suggestive and helpful.” In 1893, when Johnson brought Muir to New York to introduce him around literary circles, Kipling was one of the people he wanted Muir to meet. (In other words, Muir knew, and likely read, Kipling before writing his own masterworks. Kipling likely had not read Muir’s scattered American essays before arriving in Oregon.) Johnson is well known as the man who translated Muir’s ideas into legislation, yet he clearly loved Kipling’s ideas as well.

He was hardly the only one. Kipling, at the end of the 1889 road trip, showed up unannounced at the home of Mark Twain. Twain let him in, and they talked for two hours. In the next few years, Kipling became incredibly popular around the world. He succeeded with both the general public and high-minded critics. For example, he was the first English-language writer to receive the Nobel Prize, and still the youngest ever. Even American Notes “aroused much protest and severe criticism” at publication, according to a later reissue.

Muir achieved no such success. He was admired in intellectual circles but won no awards. His books sold well but nowhere near the level of Twain or Kipling. He unquestionably inspired leaders of the Sierra Club, and many other nature-lovers as well. But when we think about how the idea of wilderness-as-the-opposite-of-industry lodged in the American mind, maybe we need to consider Kipling.

If we do, we also end up needing to consider Kipling’s racism. Kipling’s idea of wilderness was racist, because Kipling’s ideas about everything were racist, because Kipling was such a vibrant representative of a racist society. We know this, and thus we can accept the racism of his wilderness ideas without having to besmirch anyone.

What do we do with that acceptance? I believe that organizers and activists—as opposed to those of us simply telling stories—have already made great progress. They bring nature into people’s lives, even if that means planting trees in urban neighborhoods rather than focusing on wilderness. They tamp down the discussions of “pristine, virgin” explorations, even if that means downplaying stories of masculine conquests. They look at environmental justice, even if that means addressing conditions inside the factories as well as the condition of the pines and solitude. And they see all this as consistent with keeping large tracts of land relatively undisturbed by human and/or industrial impacts—not because Muir or anyone else said so, but because it feels right.

They need more stories to backstop such philosophies. Kipling, I believe, presents a really good one.

Discussion:

I quote Kipling from American Notes (Gutenberg edition), and from a letter to Edmonia Hill quoted in the Oregon Encyclopedia. I quote Johnson from Remembered Yesterdays. For more on the Chinese workers Kipling overlooked, see Chris Friday, Organizing Asian-American Labor: The Pacific Coast Canned-Salmon Industry, 1870-1942, especially Chapter 2.

I previously wrote about Muir here, and in Natural Rivals. This essay is inspired by Richard White’s marvelous passage in The Organic Machine. (These are affiliate links.)

When I was a kid, one of my favorite jokes was: Pat: Do you like Kipling? Mike: I don’t know, I’ve never kippled.