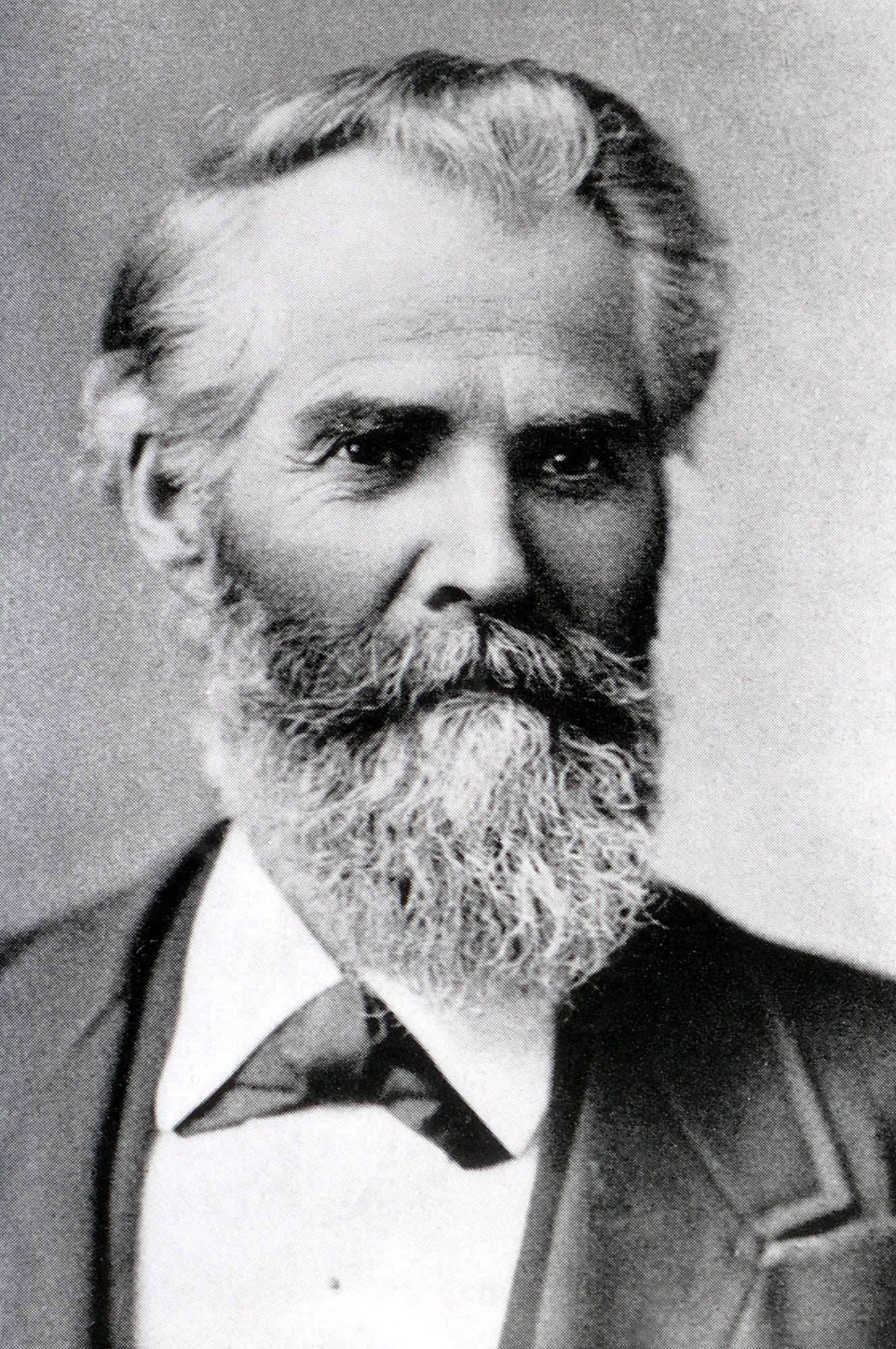

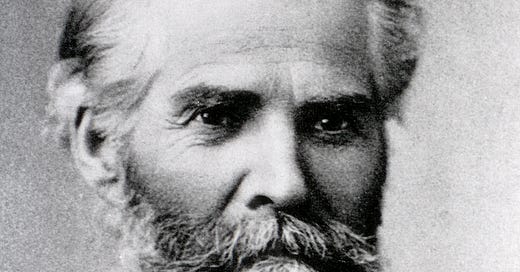

P.W. Norris shaped the natural story of Yellowstone

The park’s colorful early superintendent built roads, set rules—and created narratives, which we may now find troubling

When Philetus W. Norris was appointed Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, in April, 1877, his surprisingly difficult first task was simply to get to his workplace. From his home in Norris, Michigan (now part of Detroit), he took a steamboat to Duluth, Minnesota. There he got on a train for Bismarck, North Dakota, where the rails ended. He took another steamboat up the Missouri River to the Montana border. There, he tried to take another steamboat up the Yellowstone River, but shallow, rocky conditions made for slow going. At the site of today’s Miles City, he switched to horseback. From there it was 300 miles over unpopulated terrain to get to Yellowstone’s headquarters at Mammoth Hot Springs.

And he wasn’t even getting paid. The national park, then just five years old, had no budget whatsoever. Not for a superintendent’s salary, not for rangers, not for game wardens, not for construction or maintenance of trails or roads or buildings. His predecessor, N. P. Langford, had done the job for ego—he liked to claim that N. P. stood for “National Park.” Also maybe for some sort of private advantage: he had very close ties with the Northern Pacific railroad, which wanted a say in tourism development.

Norris was incorruptible. “He was a kindly, sincere man, whose sense of stewardship had a Biblical purity,” wrote historian Aubrey Haines in The Yellowstone Story. A teetotaler, Norris banned alcohol inside park boundaries—although of course he lacked any budget to enforce the ban. Norris was infuriated that Yellowstone was such a free-for-all. Tourists chiseled their initials into the unusual rock formations. Prospectors dug for gold. And hunters killed wild animals, almost indiscriminately. So he wanted to establish his presence on site, and build a budget to bring order. Haines wrote, “He was practical enough to see the immediate need for trails, roads, and buildings, and scholarly enough to record the area’s human and natural history; in everything he was enthusiastic and sincere, and his achievements were monumental.”

Norris did have an ego—perhaps even bigger than Langford’s. His wife and children remained in Norris, Michigan, a town he’d named after himself. Maybe he deserved the honor, after draining swamps and cutting forests to found the community. Maybe it made sense, too, for its newspaper, which he ran, to be called the Norris Suburban. But his claim that it was “widely circulated in the West” sounds like his ego talking. And of course his legacy in Yellowstone—a geyser basin, a meadow, a pass, a road, all named for him—suggests a certain pattern.

That pattern, I argue in a major article published this week, played a big role when he discovered, to his great shock, an Indigenous village co-existing with “his” park, located just six miles from his headquarters.

I won’t further summarize the article here, because I urge you to read it in full. But I would like to use this space to argue why it’s a natural story, and why natural stories matter.

Euro-American culture has long emphasized the idea that humans are separate from nature. This may be good: humans are smart, and civilized, and capable of cooperating to build great things out of mere natural resources. Or it could be bad: humans are greedy, and short-sighted, and capable of carelessly destroying beautiful and pure natural systems. But good or bad, the story differs greatly from the stories of other cultures; for example, in many Indigenous cultures, humans and nature are inseparable.

Norris embodies this natural story. He’s both good and bad. He’s smart and civilized and building great things; he’s greedy and short-sighted and destroying beautiful things.

Furthermore, he’s doing so in the context of establishing his culture’s relationships to a particularly stunning natural setting. Without Norris, you wouldn't have heard of Yellowstone and I wouldn’t be writing about it. Yet the “Yellowstone” that Norris established was a Eurocentric idea. It was full of roads and hotels and other great things that allow people like you and me to easily visit. And it presents a picture of nature as a beautiful and pure natural system, fortunately saved from destruction by people like Norris.

One thing I learned in writing this story: archeologists believe that Yellowstone is a treasure trove. Indigenous people used these landscapes and resources for thousands of years. Yet there’s very little interpretation of that: the museums and roadside signs and natural-history books are mostly about animals and trees and magma—not about the ways that people lived.

This might be good or bad. It might be good to show tourists the wonders of nature, so that we’ll be less likely to destroy those wonders. Or it might be better to show tourists how previous cultures coexisted with these wonders, so that we can use those civilizations as a model.

Either way, it’s a natural story, a story of how our culture relates to nature. Understanding these stories—and telling variants of them in varying ways—is, I believe, essential to our culture in this time of conflict. How might climate change or racial justice alter America’s relationships to nature? It’s the stories that will lead the way.

Discussion:

I quote Norris from his 1877 Superintendent’s annual report. I quote Haines from The Yellowstone Story, vol. 1.

Thanks to Mountain Journal and editor Joe O'Connor for publishing my Norris article. Here’s a third link to check it out.

Couldn’t he have taken a route to get to Mammoth (along the Yellowstone) that didn’t have any mountain passes?