Do I embrace a legend, knowing it goes against my very identity? And if not, then how will I survive?

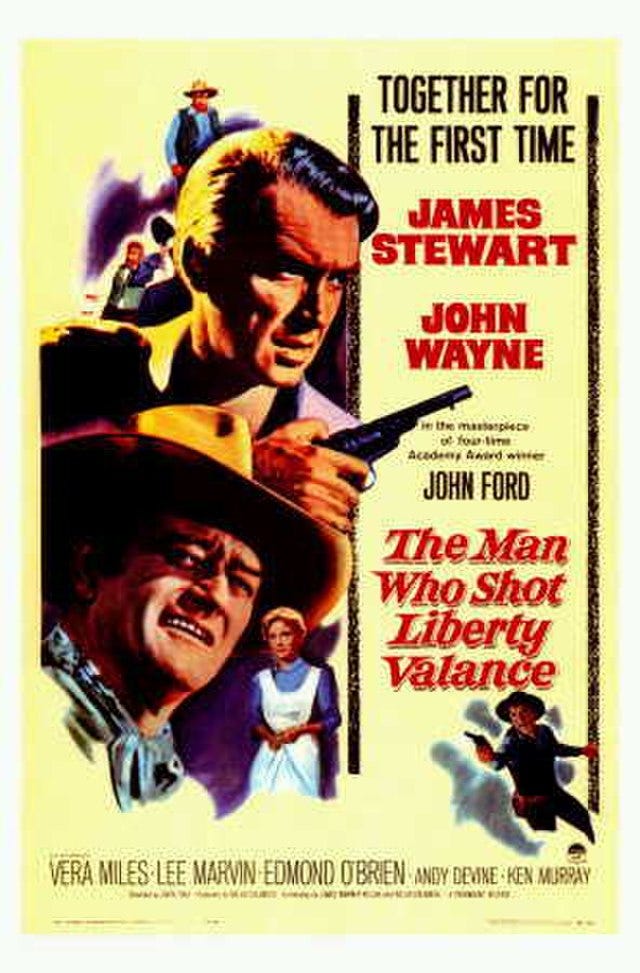

To me, the classic natural story of the Old West has always been the John Wayne–Jimmy Stewart movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. I love it for its concluding line, when a newspaperman tells Stewart (spoiler alert!) that he’s ripping up his notes of the story we just heard, because “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

That line has been interpreted literally, as questioning “the role of myth in forging the legends of the West.” And/or as a condemnation of frontier journalists willing to lie in print. And/or as an allegory for a long-broken American political system. But I see it differently.

In his great new story “Alias Curley,” author Nathan Ward describes how in the 1910s, a con man impersonated “Curley the Crow,” traveling the West to tell stories of being a scout for General Custer, fighting at the Little Bighorn, and perhaps even being the last person to see Custer alive. The con man would take loans or investments from his victims, promising adventure or riches if they visited him at Crow Agency.

The real Curley had indeed been an advance scout for Custer’s troops. But he never left the reservation, spoke little English, and never claimed to have fought in the battle itself. When you picture the con man’s victims showing up at Curley’s door, and perhaps taking out their anger on this innocent man, you can see the hideous nature of the con. The con man’s victims may have lost some money, but Curley lost his own story. His identity.

I have argued that something similar happened to Calamity Jane. She’s one of the most famous women of the Old West because of the stories that were told about her. Yet those stories were the fabrications of dime novelists. Martha Jane Canary never had the ability to control how society perceived her.

Note how these thefts targeted the least powerful members of society: women and Indigenous people. They lacked the education, the fancy lawyers, or the cultural cachet to be able to have a fair fight with the prevaricators who took not their money—they had none—but something more essential to their lives.

That’s why I’m especially haunted by a line in Ward’s article: “Curley gradually stopped correcting the stories that came back to him on the reservation, and occasionally echoed familiar newspaper versions. Mostly, his silence became assent.”

Calamity Jane did the same thing. If she was going to be the most famous woman in the West, she decided, she should make money at it. So she published an “autobiography” that echoed the stories others had told about her. Then she went on tour to tell those stories in person.

And since none of those stories were true, people became disgusted with her. How could you lie about your own story? Yet she was only submitting to the lies of others. How could you collaborate with these evildoers who stole your identity? But they had gotten away with it! How could you give up who you were? She has come down through history as a far more morally questionable figure than any dime novelist.

But what other choice did she or Curley have? “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend” isn’t only a comment on journalism or Hollywood or history. It’s a depiction of the appalling moral choices faced individually by all sorts of people in the Old West. In Liberty Valance, the characters played by Stewart and Wayne were easy for 1960s audiences to identify with, because they were upstanding white men. But if we can also identify with members of the West’s marginalized populations, then maybe we can more easily transfer these lessons to a wide variety of locations still today.