Johnny Appleseed, businessman and spiritualist

Why do we know his legend? (Related: What was his relationship to nature?)

The legend of Johnny Appleseed is one of America’s favorite myths. But did you ever stop to think about his business model? Or his unusual ideas about God?

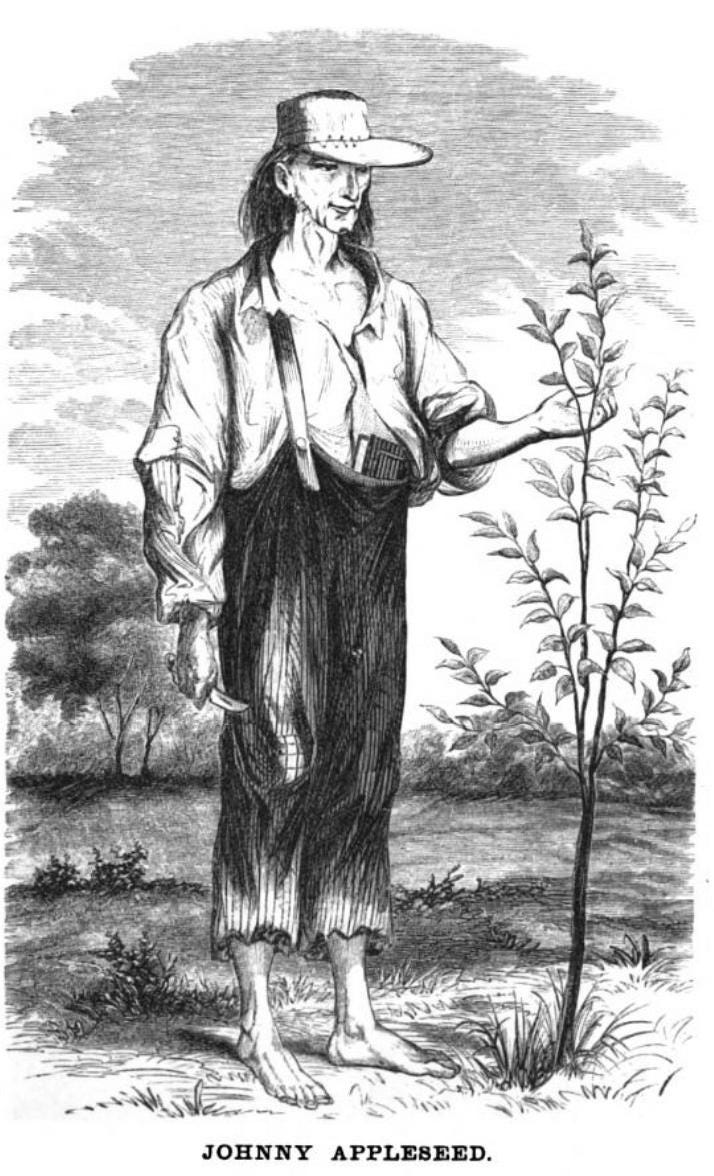

Though clearly exaggerated—it’s really uncomfortable to wear a cooking pot for a hat—the Appleseed story is based with remarkable accuracy on the life of John Chapman (1774–1845). In the early 1800s, Chapman wandered through frontier Ohio, planting apple seeds. He never married or had children. He was basically homeless, always sleeping outdoors or in the shed of a friend. He thus wasn’t part of accepted society, more of a Wilderness Man.

Yet he wasn’t like other wilderness heroes, conquering fierce beasts or people. He was meek and kind and playful. A friend to animals, he may have even been a vegan. He tamed the elements through plantings rather than muskets.

Make no doubt about it: he caused native ecosystems to suffer. He brought appleseeds from elsewhere—invasive species—to help other white people turn traditional forests into predictable farms. And while most of those invaders got rich in the process, Chapman acted as if he’d taken a vow of poverty.

I believe that people of Johnny’s era told stories about him because they were trying to puzzle out his relationship to society. Chapman’s contemporary James Fenimore Cooper (1789–1851) wrote a series of Leatherstocking Tales (the series included the book Last of the Mohicans) about Natty Bumppo, a white man raised by Indians. Bumppo symbolized vanishing wilderness yet he was also an interpreter and guide for white men seeking to conquer that wilderness.

Like Bumppo, Appleseed was a Moses leading his people to a Promised Land that he would never see. Or perhaps even want to live in. The Bumppo/Appleseed types were essential to the expansion of white America at the time. But what motivated them? Not money. Nor fame. Not preservation of the old ways, nor “progress” for its own sake. Trying to figure these folks out, people told stories about them.

To pay his expenses, Chapman sold seedlings. In other words, his business model was to go out into the wilderness, plant some appleseeds in suitable places, and then come back every few months or years to clear weeds out of the grove. Years later, settlers would move in, and Johnny would sell them partially-grown trees for three to five cents apiece.

It was a good deal for the settlers, who wanted pies, tarts, and especially cider. Some homesteading contracts even required the planting of fruit trees, to discourage speculators. But carrying your own trees took up too much space in your wagon; planting your own seeds was too risky. Buying them from Johnny meant instant civilization.

Johnny was erratic at business. Sometimes he charged market prices, sometimes he gave away seedlings because the buyers seemed poor, and sometimes he traded for food, shelter, or IOUs. He often neglected his groves, which became weed-choked, eaten by browsing deer, burned in a fire, or claimed by an incoming homesteader. Johnny usually just shrugged and moved on.

It was easy to move on. He almost never owned the land, and he recycled appleseeds from cider mills, so his capital expenses were negligible. His only investment was time, and time wasn’t a burden because he loved planting appleseeds.

The trouble was, growing apple trees from seeds was an incredibly inefficient way to produce apples, most of which tasted terrible. The fruit industry was then being transformed by industrialization of the process of grafting. It’s more efficient to meld a good-tasting apple branch onto a tough old rootstock. But Johnny had no interest in grafting.

According to one rumor, his religion prevented it. As with any great American story, Johnny’s was complicated by an intense relationship to theology. He was a follower of Emanuel Swedenborg, a deceased Swedish physicist. Swedenborg believed that everything in nature had a deeper spiritual meaning that could only be expressed through complex intellectual “correspondences.”

“For example,” writes the Swedenborgian Appleseed biographer Ray Silverman, “a seed falling on the ground corresponds to truth presented to the human mind. If the seed (truth) falls on good ground (a good heart), it will blossom and bear fruit.” Any natural process is thus “a living sermon from God about how truth can be received and bear fruit in human beings.”

Johnny’s wanderings were thus a form of pilgrimage. Indeed, he carried Swedenborg’s books with him. He handed them out to everyone he met. He was, like many of his contemporaries in the Second Great Awakening, primarily a rural evangelist. Selling apple seedlings was a sideline, and most of its revenues went to purchasing more religious tracts.

When I first learned this—given the poor reputation of evangelists today—it made me uncomfortable. We perceive Johnny as a wilderness figure, and isn’t wilderness about science? Or at least about individual spiritual relationships? Why would you need a deceased Swedish physicist to intervene with a set of intellectual correspondences?

But then I realized: Johnny was probably drawn not to how Swedenborg saw God, but how he saw Nature. They both saw Nature as the best place to experience God. Likewise, Johnny was drawn to planting appleseeds not as a way to make a living, but as a way to make a life. In Nature, he believed, was the best way to make a life.

Unlike the people telling stories about him, Johnny wasn’t terribly interested in his relationship to either religion or society. More important was his relationship to nature. And that’s why his story endures.

Notes:

I learned most of this from William Kerrigan’s fantastic book Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012. (That’s a bookshop.org affiliate link)

I quote Ray Silverman from The Core of Johnny Appleseed: The Unknown Story of a Spiritual Trailblazer, West Chester, PA: Swedenborg Foundation Press, 2012, p. 55, emphasis in original. (That’s a publisher link.)

This is an excellent portrait of an enigmatic figure from the early 19th century known mainly through apocryphal legend rather than biographical facts. I haven't read the two books you cite, but Leigh Schmidt's book "Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality" discusses Chapman's Swedenbourgian influence and some of his bizarre theological interpretations. Also, regarding American Protestant evangelicalism, its 19th-century origins were quite different from the ultra-conservative, literalist interpretations that developed in the 20th century. Evangelicals were at the forefront of many liberal movements of the 19th century, including abolitionism and women's rights.

Interesting read. Chapman may have been somewhat of a land speculator, and possibly better off than the image of poverty we associate with him. Regardless, I'm not sure the nice myth about Johnny Appleseed outweighs the impact he had by introducing non-native species to an area, especially in hopes of attracting more Europeans (even though most of the Native Americans who were managing the land had been killed off one way or another). He introduced plants besides apples. Including dog fennel, which is a problematic "weed" in many places. Of course, apples, whether edible or not, were used to make the hard cider that was so ubiquitous at the time, in part because safe drinking water was often not readily available. Eventually the temperance folks came along and, among other things, tried to give apples a bad name. After prohibition it took campaigns like "American As Apple Pie" to help rehabilitate the apple. Part of the innocent appeal of the Appleseed myth is typical of myth. You think of Appleseed and you think of innocent and wholesome settlers setting delicious apple pie on the kitchen windowsill to cool. The reality is much different, and less admirable, as it usually is with myth. Interesting info on his theology. "The Core of Johnny Appleseed." What a great book title! Of course, I give him points for not eating meat.