F. Scott Fitzgerald’s wilderness cosmology

In Montana, the writer saw wilderness as a way to critique society

In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Montana, the sunset “lay between two mountains like a gigantic bruise from which dark arteries spread themselves over a poisoned sky.” A village named Fish was “minute, dismal, and forgotten.” It consisted of just twelve men, “a race apart… like some species developed by an early whim of nature, which on second thought had abandoned them to struggle and extermination.”

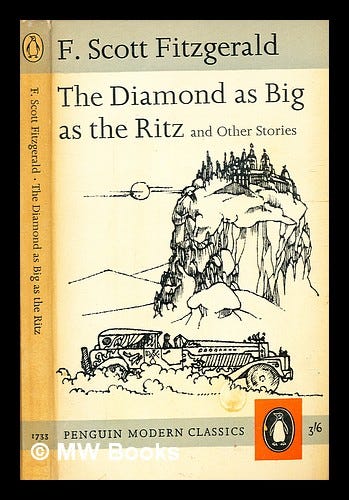

These descriptions come from “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” a novella published in 1922, near the height of Fitzgerald’s fame. He’d already published two novels and a collection of stories; he lived a glittering New York life while critiquing its excesses in his fiction. “Diamond” is classic social satire, in which rich people become monstrous by pursuing ever more money.

The story’s narrator visits his classmate’s family home, where he discovers that they own a mountain consisting entirely of a gigantic diamond. Though Fitzgerald doesn’t use the word wilderness, he conveys it through details. For example, this is the "only five square miles of land in the country that's never been surveyed." The family keeps African-American slaves, having told them that the South won the Civil War and kept them away from any outside influence that might say otherwise. The family commits frequent murders to ensure that the source of their everlasting wealth remains secret. In the end (spoiler alert!), word gets out; an attack is launched; the family decides to blow up themselves, their slaves, and the mountain rather than let others get hold of it; and the narrator and his friend’s two sisters barely escape.

To most critics, the point is not the plot but the gorgeous sentences and the world-view. Fitzgerald was writing near the peak of the Ku Klux Klan’s popularity, and in the aftermath of the 1914 Ludlow Massacre in Colorado, which culminated a two-decade period when America was closer to an literal class war than at any time before or since. He was astonished at how little rich people seemed to care about anything but money.

Some critics focus on the biographical: Fitzgerald himself had been raised middle class and twice rejected by wealthy women. In one case, her father allegedly said, "Poor boys shouldn't think of marrying rich girls." He had an envy-tinged bias against the upper classes. And when he was in college, he spent a summer in Montana visiting the family ranch of a wealthy classmate. He probably visited a ghost town called Diamond City in a valley called Confederate Gulch.

But what strikes me about Fitzgerald’s Montana—his wilderness—is how fantastical it is. The family compound features a futuristic automobile, a perfectly manicured golf course, and individualized movie theaters. The wealthiest family in the world has built a techno-utopia, and located it in the middle of nowhere to keep it a secret.

Plenty of people might usefully ask: is that how we see rich people today? I’d like to ask: is that how we see wilderness today? A utopia held apart from society, and thus pure. The wilderness in “Diamond” was built around greed and evil, by monopolistic, slave-owning murderers. Some of us want to believe that by contrast, today’s wilderness is built around the virtues of nature and science and democracy.

Ideas of “wilderness,” as opposed to “nature” or “the middle of nowhere,” often imply a cosmology—a theory about the origins of the world. For white American nature-lovers, wilderness reflects our understanding of a world that originates in ecological science. (Or maybe a Biblical Garden of Eden. Or maybe a lawless, anarchist place that’s the opposite of society. There’s some cosmological conflict.) Those meanings of wilderness prove difficult to translate into other cultures that come with other cosmologies.

But Fitzgerald wasn’t particularly a nature lover. For example, he apparently spent most of his Montana visit in the town of White Sulphur Springs, rather than cowboying on the ranch four miles east. He was hardly roughing it: he stayed in a castle and went to movies and theatrical productions.

Thus his cosmology of wilderness differed from those of hikers or horse-packers or scientists or cowboys. Or Native Americans or African Americans.

Fitzgerald wasn’t interested in wilderness as chaos or the uncontrollable. Nor as beauty or ecological process. Nor as a test of athleticism or manhood. Nor as a source of spiritual wonder. For Fitzgerald, the purpose of wilderness was to serve as an allegory: a place where we could tell stories about society.

The place didn’t really exist and thus didn’t need to be managed or preserved. It could be populated by people who fulfilled odd stereotypes. Its sunsets could be bruised, dark, and poisoned, its local residents doomed to struggle and extermination, its overlords absurd caricatures of people back in New York.

Allegories play an important role in societies. America’s other allegorical places have included outer space, the courtroom, and the Old West. But when we enter a real-life courtroom, do we expect it play out like it does on TV? When we enter a wilderness, do we expect it to match the allegory in our head? And how often do we impose that cosmology on others?

Discussion:

I quote Fitzgerald from “Tales of the Jazz Age/The Diamond as Big as the Ritz”

For the fascinating story of Fitzgerald in Montana, see this video of a presentation by Stu Wilson and Melissa Barker at the 2023 Montana Historical Society conference.

Good read. "Diamond" sounds like it could have been used for part of the storyline for the Yellowstone series. Wondering if wilderness isn't those parts of the landscape that Native Americans weren't able to manage with fire (or what resulted when Native Americans were killed off and were no longer managing the landscape with fire, especially in the Eastern U.S.).