Charley versus nature

Heralded as an American classic, even a classic of nature writing, John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley is a natural story in the sense of not really being about nature

Charley “shrieked with rage… He screeched insults… he cursed and growled, snarled and screamed.” Charley was an otherwise mild-mannered standard poodle riding in a pickup truck with a campertop. “I was never so astonished in my life,” said his owner.

They were in Yellowstone National Park in the fall of 1960. In Yellowstone in that era, black bears would amble along the side of the road, and even come up to your car to beg for candy. Charley didn’t like bears. Even though he’d never met one, even though “his whole history had showed great tolerance for every living thing,” even though he was “a coward, so deep-seated a coward that he has developed a technique for concealing it,” he acted like “a primitive killer lusting for the blood of his enemy.”

Charley ruined the park for his owner. “No amount of natural wonders, of rigid cliffs and belching waters, of smoking springs could even engage my attention while that pandemonium went on.” They drove right back out of the park, and made sure to stay that night in an urban spot where Charley wouldn’t be bothered by bears.

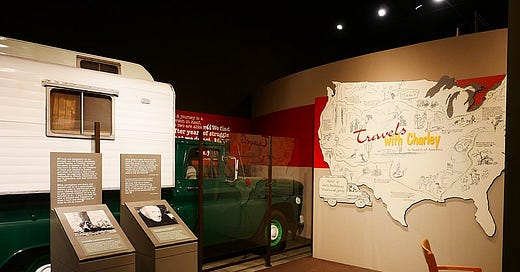

Charley’s owner was the author John Steinbeck. He recounted this story in the memoir Travels with Charley: In Search of America. The book is fondly remembered for all the best reasons: it’s the chronicle of an old man trying to reconnect with the nation he loves, with the salt-of-the-earth folk who had inspired his great novels The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden. We admire Steinbeck’s humor and melancholy and his adventurous spirit. We overlook the synthetic wooden dialogue and several howling fictionalizations.

Steinbeck was shy and lonely and worried that his writing style was becoming unfashionable. He was sickly, maybe dying. But worse, he was afraid he was losing touch with the people. His trip reflected a desperate need to find a “real” America that resembled the one he grew up with. His results were mixed—but the search itself is what enthralls us.

It certainly enthralled critics of the time. The year after the book’s publication, Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize. One critic said that once Steinbeck got west of Chicago, the book became “an unabashed love affair with nature.” Which is odd: not only did Charley dislike bears, but also Steinbeck disliked national parks. “Yellowstone National Park is no more representative of America than is Disneyland,” he wrote. He didn’t want to see its natural wonders; he was thinking only of the FOMO he would experience in conversations with friends after he returned home.

Nor did he care for the Continental Divide, which he crossed at Montana’s Pipestone Pass: “I saw in my mind escarpments rising into the clouds, a kind of natural Great Wall of China. The Rocky Mountains are too big, too long, too important... the place wasn't impressive enough to carry a stupendous fact like that.”

Yet he never left his car to get out in those mountains. He didn’t fish, hunt, hike, swim, ride horses, float rivers, or even much stretch his legs while admiring a vista. He bought a hat in Billings, a jacket in Livingston, and a rifle in Butte, but all were just excuses see how people were living. Traversing a vast countryside, he was drawn to the human settlements.

In a letter, he wrote that eastern Montana was “huge and largely impractical. Lots of sugar beets. Lots of small bars in the towns. I stopped in about six. Little square, burnt-up men with little speech, all bent and warped with riding and sun and also cold, faces very red.” He saw nature in the people—mostly, following the sad standards of his day, in the white men.

He cited Montana’s “grandeur.” (My favorite line: “Montana seems to me to be what a small boy would think Texas is like from hearing Texans.”) But he described that grandeur in faces and voices and attitudes rather than wildlife or geology or ecosystems. “The calm of the mountains and the rolling grasslands had got into the inhabitants,” he wrote, delighted that Montanans had “a definite regional accent unaffected by TV-ese” and “did not seem afraid of shadows” the way some conservatives of the era feared Communists around every corner.

For some people today, nature is separate, different, a national park, west of Chicago, a bear beyond the windshield to prompt unexpected emotions. This was the “nature” that Charley didn’t like—and that Steinbeck found boring compared to Charley’s personality. “That dog has the heart and soul of a bear-killer and I didn't know it,” he claims to have told a ranger on his way out of Yellowstone. He summarizes the moral of his story the next day: “In the morning [Charley] was still tired. I wonder why we think the thoughts and emotions of animals are simple.”

Steinbeck was a natural storyteller. Yet even his love affair with nature consisted of stories of people and pets. Should we criticize him for that, complain that in describing only human culture, he had missed the landscapes and thus had not really seen America? Or should we criticize the nature-writing purists, and complain that in venerating nature-as-other, we are not really seeing Americans? Which are the natural stories?

Notes:

I wrote about Steinbeck in Montana for Montana Quarterly magazine in 2015, arguing that Charley’s great accomplishment was to capture—alongside Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, from 1957—the last gasp of an old style of auto touring, soon to be sidelined by the Interstate highway system. It’s available only to subscribers.

One of my sources for that story, Bill Steigerwald, tells some of his stories on Substack.

I’m quoting Steinbeck from Travels with Charley and from Steinbeck: A Life in Letters (p. 689).

Sending this on to a friend who also admires Steinbeck, Paul McComas

Do you know the story behind this novel? https://nps.edu/documents/110773463/139608448/THE%20WRITTEN%20WORDThe%20Moon%20is%20DownBy%20John%20Steinbeck.pdf