Can capitalism save the climate?

In which our hero, on the biggest stage of his life, decides to take an unpopular stand for the environment

The physical stage at the Wilma Theater in Missoula, Montana, is huge. When the Los Angeles Philharmonic performed at its opening in 1921, the whole orchestra fit on the stage. The Wilma still hosts plays, concerts, and other lots-of-people-on-the-big-stage events. But because Missoula is such a literary town, I’m often there to see a sole writer, or maybe a panel of three or four, looking lonely in that vast expanse. It’s quite an honor, to address a 1400-seat hall. Of the twenty or thirty writers I’ve seen talk there, probably half have commented on the area’s expanse, the brightness of the lights, the distance from the audience—I hear them coming to grips with being on that big stage.

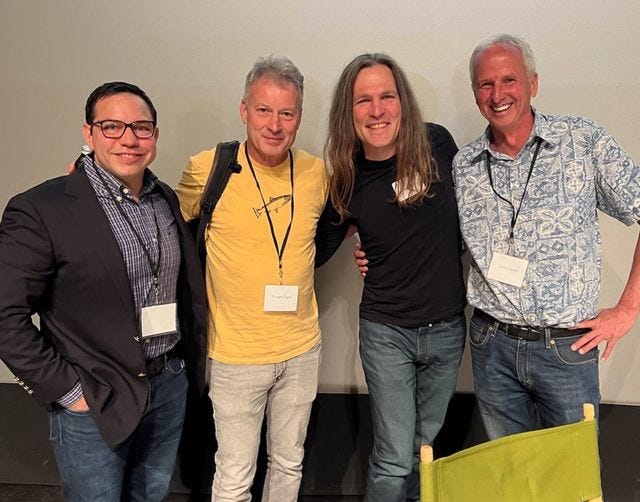

In June 2022, when I was invited to participate in a panel on that stage, I was thrilled. Most of the other writers involved were more famous than me. Some were my longtime heroes. And the event—the In The Footsteps of Norman Maclean Festival—honored Montana’s ultimate natural storytelling icon.

The event’s uplifting theme, Public Lands and Sacred Ground, was a good fit for my then-recent book Natural Rivals, which explored the origin of public lands. But the crowd’s mood was apprehensive, maybe even clinically depressed. The world seemed faced with unsolvable problems, such as climate change, racial justice, and fascist tendencies. After Timothy Egan offered an opening keynote address based on his book The Big Burn, an audience member asked if Egan could provide any sort of hope in the current era, a “reason to get out of bed in the morning.”

Later, when he was moderating our panel, Egan turned the question around to us. “Can you give me any reason why climate change won’t be a force that’s greater than anything we can do politically?” Where did we see the hope?

My co-panelists bravely talked about supporting and participating in democratic processes, and supporting and participating in projects to improve the environment. They wanted to give this audience what it needed. But as I listened and waited my turn, I was internally torn. I had a different answer to this question. It was one I firmly believed in—but one I suspected the audience wouldn’t like.

Literary events always feature panel discussions. Some of them are quite dreary, as the panelists don’t know how to engage each other. (After all, they’re writers, used to explaining their ideas alone and with plenty of revision time, not on the spot with others.) But this panel had so far lived up to the promise of the format, thanks in large part to Egan’s moderation. He asked us challenging questions. He made us think fast. He made us engage with himself, each other, and the audience. He also built an atmosphere of trust, making me willing to go out on a limb.

“As much as I love democracy,” I said, “the other big force that governs our lives is capitalism.” My day job, I explained, involved writing marketing materials for high-tech and consulting firms. For more than a year, I had been writing solely about how and why companies could reduce their carbon footprints—and the reason I was writing these materials was that companies kept asking my clients for them. Because taking action to decarbonize was what their own customers and shareholders and funders were demanding from them.

At a literary event in a university town, the audience was full of good, earnest Progressives. They believed in democracy. Whenever a problem arose, their first instinct was to ask how democracy could fix it. And I asked if that might not be the only answer, if maybe some problems could be fixed by markets. “We often focus on democracy because we can vote, and yet when we buy things, that is a form of voting, that is a set of institutions that must respond to our values.”

I’ve always loved Missoula because it’s full of hippies, but they tend toward anti-capitalism. I sympathize with these views; capitalism can be a cruel system. But I sometimes wondered how many people saw the climate crisis as yet another hammer they might use to beat capitalism. It seemed to me that scientists were telling us that things should work the other way around: the climate crisis was existential. It thus couldn’t be a tool to a greater goal. It was the greatest goal, for which all available tools were needed.

“Although capitalism did a lot to create this crisis, it may be possible for capitalism to help solve this crisis,” I said. I’d heard plenty of socialists arguing the opposite: that capitalism couldn’t solve the climate crisis since capitalism was the cause of the crisis. But didn’t democracy, too, play some part in causing the crisis? Few people wanted to argue that democracy was incapable of solving it.

Egan asked me about the clothier Patagonia. I said it was a great example of a company that made money by listening to its customers, who wanted a healthy environment. He agreed, but wanted to talk about politics. “They led the charge against the Bears Ears rollback,” he said, referring to Patagonia’s advertisements criticizing Donald Trump’s drastic 2017 reduction in the size of Bears Ears National Monument in Utah.

This was not where I wanted to go. “As journalists and activists, we tend to focus on the political realm,” I responded. Personally, I’d opposed the Bears Ears rollback. I was glad when Patagonia spoke up against it. But the way to solve climate change wasn’t to convince companies to take political stances—as if the political realm was the only one that mattered.

When it comes to the climate, action is the realm that matters. Companies must be convinced to change their operations to reduce carbon impacts. Patagonia has admirably both talked the talk and walked the walk. And yet even though the latter is far more important—and, I would argue, far more technically difficult—journalists and activists keep dwelling on the former. “There’s a more holistic view of getting in touch with your customers’ values in general,” I said. “Whether or not a company makes a political statement, if they can reduce their carbon footprint, they will help us in this fight against global warming.”

I’m not telling this story because I need to convince you that I’m right. (I have opinions, and I think it’s important that the discussion include them. But when it comes to such big problems, any of us could be wrong.) I’m sharing because of how I felt when I walked off that big stage. My body and spirit felt integrated, peaceful, and whole. I was energized but calm, self-contained but curious, not sure how well I’d done but without a scrap of regret. That feeling is what makes this a natural story.

I had faced a dilemma: would I really speak up and tell these people—these friends and heroes—something that I feared they didn’t want to hear? Would I really stake out a public disagreement with our exemplary moderator, a Pulitzer Prize–winning former New York Times columnist whose books I cherish?

I made a choice. I spoke from my heart. I spoke for my beliefs. Afterward, I felt like an athlete who’d just competed in a championship, a CEO who’d just taken the company public, a candidate who’d just marked the ballot with her name, a lover who’d just proposed marriage. It doesn't matter if you win or lose. It doesn't matter if the stock price goes up or anyone is swayed by your opinion. It doesn’t even matter all that much whether your lover embraces the ring. What matters is the moment, your preparation for it, and your appreciation of it. When you choose to bring your whole self to it, and stay true, a natural story will emerge.

Discussion:

The event was two years ago today. And the Maclean Festival has just announced its next event, September 27–29. Although I’m not involved, the details are here.

A history of The Wilma is at https://theclio.com/entry/88783

If you want to watch my choice in the moment, check out 2:14 to 2:16 in this video of our panel.

Good for you, John!

There is, of course, a difference between using markets as a tool to address issues that are amenable to that approach and using capitalism - which as you say can be cruel - which is a particular political system camouflaged as an economic system.

A great example of how intellect, passion, and courage can align to make the world a better place