A natural history of George Washington’s cherry tree

Why so much focus on the boy’s honesty? The tree can tell us much more about our nation

Most of us learned as children that George Washington, at age six, chopped down a cherry tree. When confronted, he confessed: “I cannot tell a lie.” His brave honesty melted his father’s anger and set the stage for future greatness.

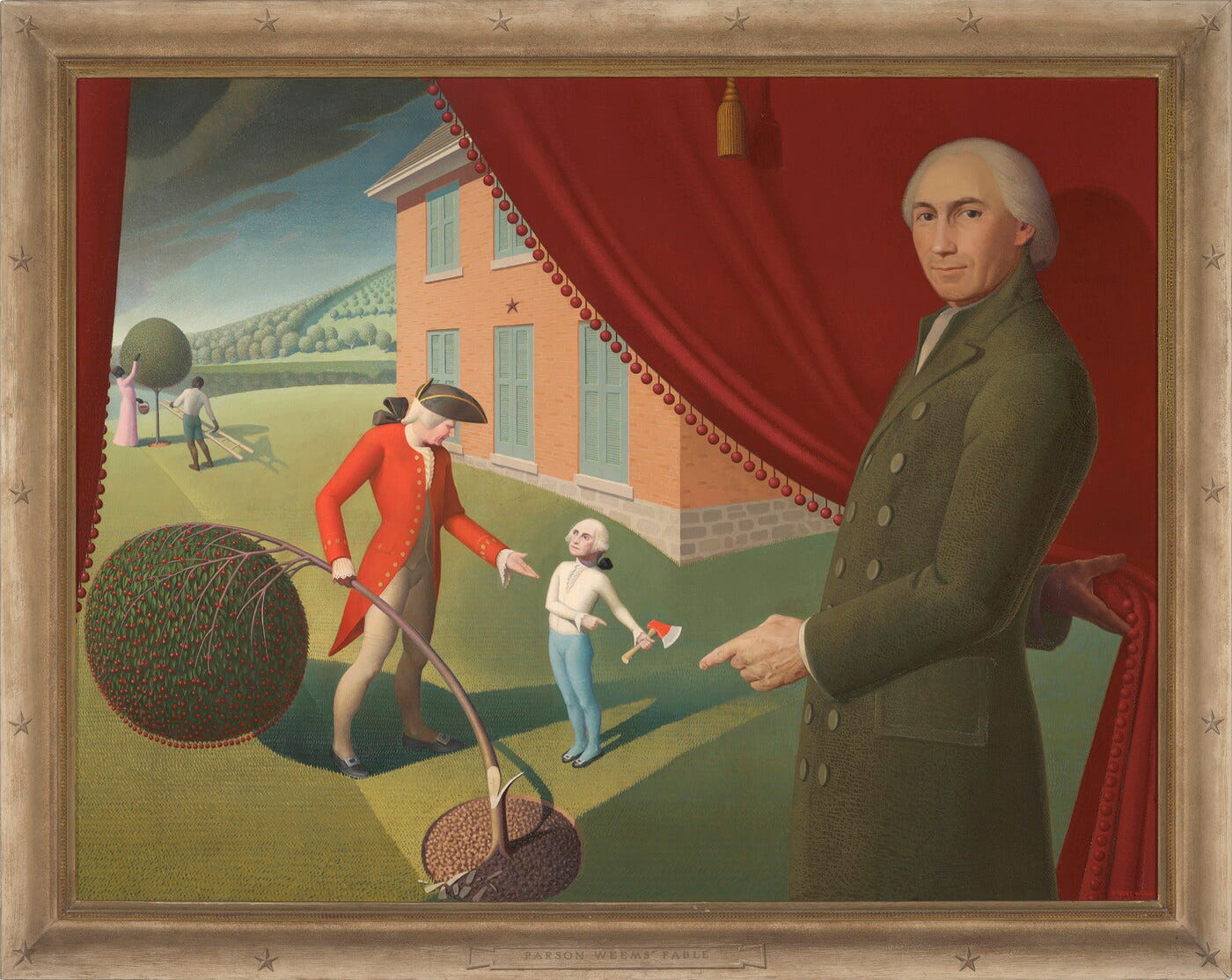

Many of us later learned that this is all hogwash. The story comes from a quickie biography published immediately after Washington’s death (actually from a later revision of that book). It was authored by Mason Locke “Parson” Weems, a notoriously sentimental moralist and plagiarist who never met Washington. Weems claimed he had a source, an unnamed “excellent lady,” and what he actually wrote may have even been true. But the tale was later embellished by people who knew the value of a good story.

Much of the value of that story comes in its specificity. Weems explains that young George had just been gifted a hatchet, “and was constantly going about chopping every thing that came in his way.” You can picture the young boy, momentarily unsupervised in the garden. His hatchet's last victim was “a beautiful young English cherry-tree,” a great favorite of Augustine “Pa” Washington, and worth more than five guineas (perhaps $100 today). When confronted, young George had “the sweet face of youth brightened with the inexpressible charm of all-conquering truth."

The specifics are clearly in service of a moral: this anecdote is preceded by another one where George and his father talk about honesty. Readers lapped this stuff up: here were intimate stories of a Founding Father’s family life. The stories were made especially poignant by the fact that Augustine Washington died when George was just 11—but maybe his early-parenting talent had been essential to the nation’s future.

As a general and President, George Washington was generally a rather distant figure, which may help account for the many myths that arose about him. He didn’t have wooden teeth (they were fake, but not wood); he probably didn’t pray at Valley Forge (another story for which Weems is the only source); he was never exactly offered the chance to be king (though had he been interested, likely nobody could have stopped him). His outward actions were noble and unexplained. Myths explain.

But they also obscure. Consider, for example, the cherry tree. It was not, as we might want to imagine, the flowering variety that draws today’s tourists to the nation’s capital, including the Washington Monument, each spring: those are Japanese trees (Prunus serrulata), imported beginning in 1912. Nor was Washington’s a wild, native tree, such as a “rum cherry” (Prunus serotina) with its rich wood and bitter fruit, nor a chokecherry (Prunus virginiana), shrublike and even more bitter.

Instead, Weems specifies that it was an English cherry tree. Wild cherry trees were native to most of Europe, including Britain. But cultivated varieties were popularized in England during the Roman Empire, and again in the 1500s by Henry the Eighth. Most were sweet cherries (Prunus avium, confusingly often called a “wild cherry” even though it’s now usually cultivated) but some were sour cherries (Prunus cerasus, likely a descendant of the sweet cherry).

English settlers began bringing cherry seeds to North America in the 1620s. The cultivated sweet or sour cherry tree is thus an artifact of settler colonialism. The tree shows a great deal about the Washington family’s values: they favored English imports over natives.

The tree also shows their social status. Like apple trees, cherry trees grown from seeds are unpredictable—their fruits won’t necessarily taste like the fruit they came from. So most farmers who planted seeds likely tossed them around randomly, hoping that if the fruit was inedible, it could at least serve as animal feed.

By contrast, according to the National Park Service, some wealthy colonists designed “fruit gardens.” These trees were heavily managed. Limbs of desirable sweet or sour cherry trees—"dessert cherries”—might be grafted onto hearty rootstocks. If your goal was to easily pick fruit, you might choose a dwarf rootstock. If your goal was a tall, beautiful tree as the centerpiece for a garden, that too came from your rootstock.

Augustine Washington was the sort of man who might have had such a fancy garden and treasured the trees within it. (Indeed, in 1762, the adult George himself noted receiving some cherry trees to plant in his garden.) At Ferry Farm, Augustine grew tobacco, corn, and wheat on 280 acres, plus 300 adjacent rented acres. He also produced iron and wool. The family lived in an eight-room house, complete with a 16-square-foot root cellar. They were not wealthy enough to easily survive Augustine’s early death—George had to learn the craft of surveying at age 16—but likely wealthy enough to be proud of a fruit garden.

However, the Washingtons didn’t move to Ferry Farm until the very year of the alleged cherry-tree story. So how would Augustine have developed a garden and five-guinea tree there? Yet if the story took place at Mount Vernon, where the family lived before Ferry Farm, it’s hard to know much about the setting. George made substantial renovations to the grounds when he lived there as an adult. And when he briefly lived there as a kid, nobody dreamed that anyone would later care about the location or condition of its cherry trees.

All of this has a caveat, of course: Parson Weems may have made it all up. The Washingtons may not have had any fruit trees, much less a five-guinea one that Augustine was proud of. He may not have been an expert horticulturalist, or had a sweet tooth. George may not have chopped anything down, or later discussed such events with his father.

We are often drawn to stories that purport to explain people. That’s not surprising: we ourselves are people, and thus imagine that such stories can help explain ourselves. But people are messy, complicated, contradictory. Sometimes, pulling the lens back to look at the ways people interacted with nature—the natural stories—can be even more instructive.

Discussion:

Interesting story on many levels. A personal tie also for me: from 1972-1976 I lived in a subdivision in Stafford County, VA, called "North Ferry Farms" and spent my sixth grade year at Ferry Farms Elementary. Any story with a reminder that we humans are messy wins my vote. Thanks for writing it.